Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

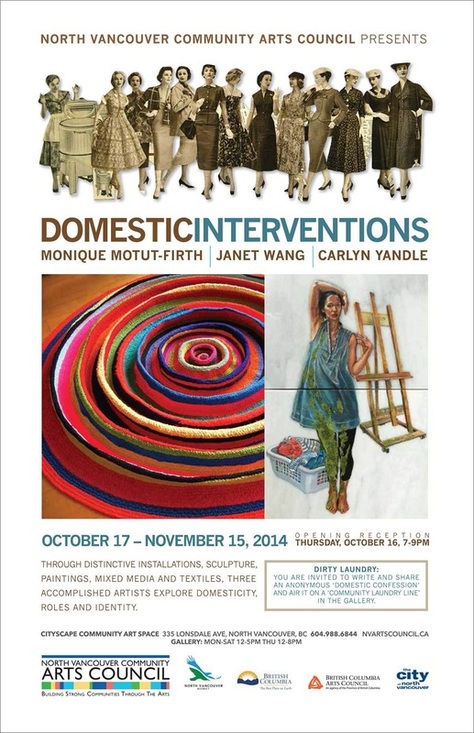

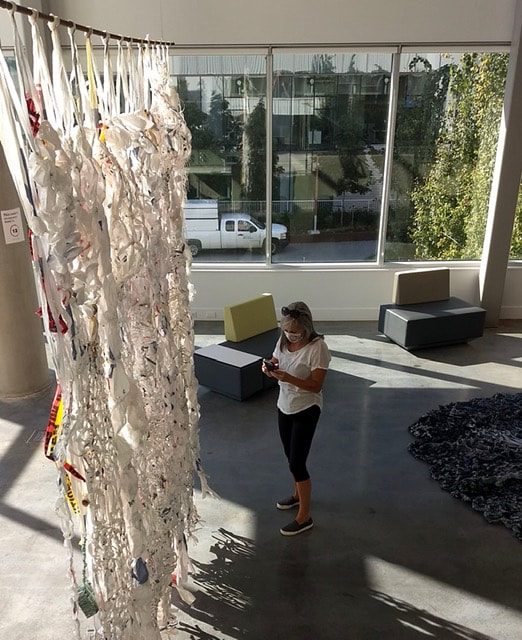

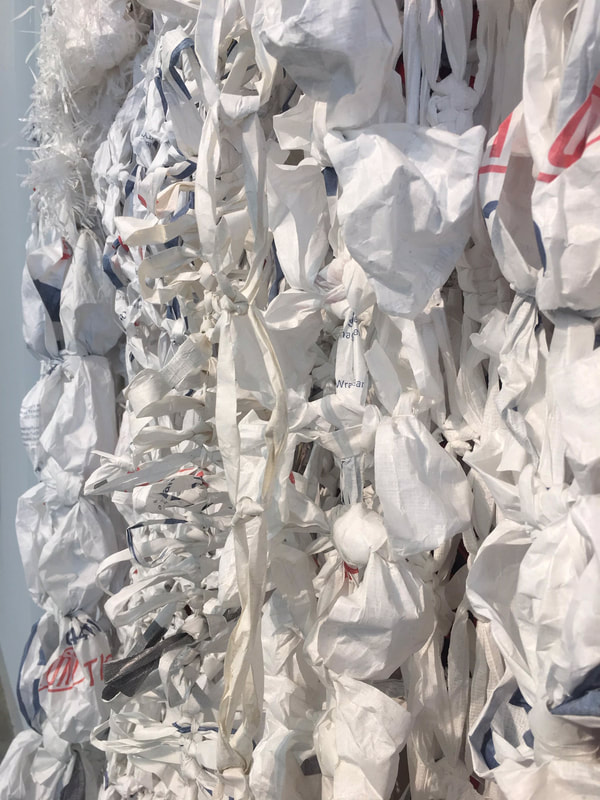

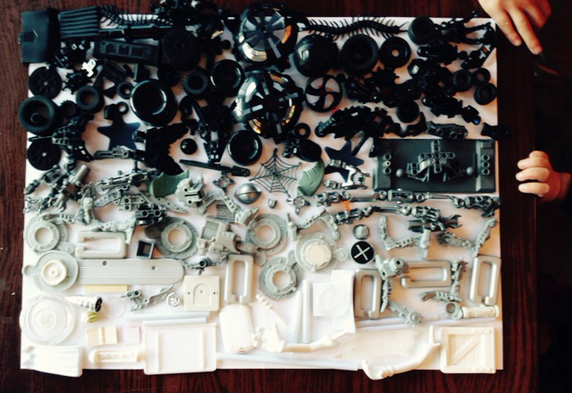

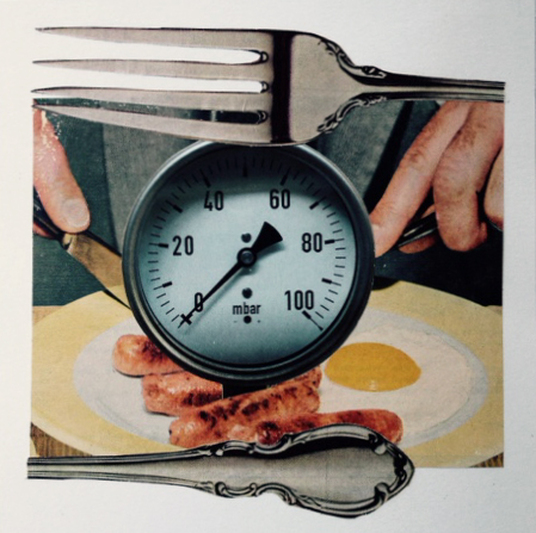

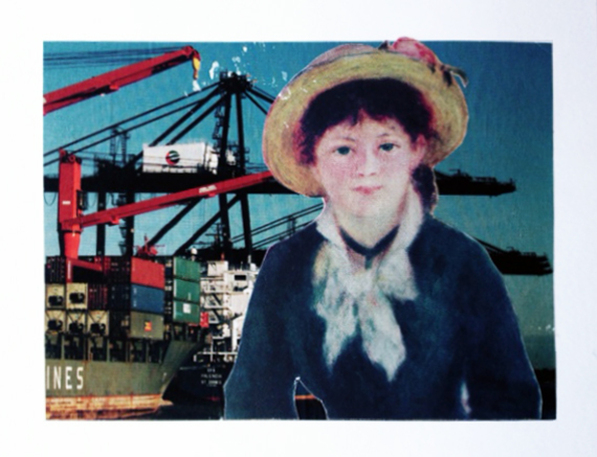

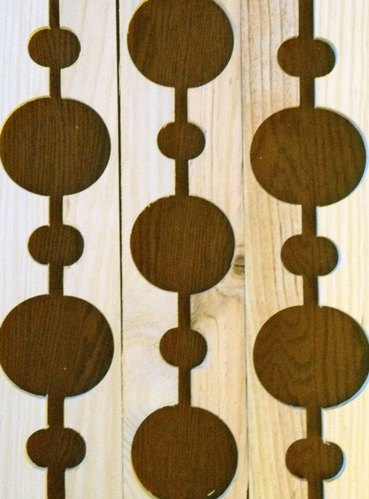

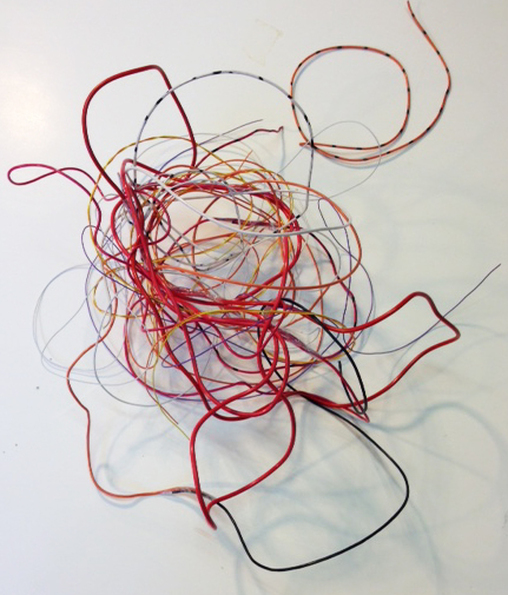

Where is the joy when you’re living in a time of a global coronavirus pandemic and a local toxic-drug epidemic? What is the use of making when your city is seized by global investment-real estate schemes, when there’s too much stuff in a overheated planet and a hateful, superpower president next door? These questions ricochet around my brain, only abating when this futile, exhausting expenditure of energy hones in on the rote activity of knotting and needleworking. The hand-wringing falls into rhythm as I grasp at lost, tossed threads that I make whole and into whole new ideas. Making is a very personal physical reaction to perilous times and unstable circumstances but working with found fibre is also an intrinsically social action that weaves in disparate economic circumstances, language, race, age and abilities. Braiding, stitching, knotting, needleworking create resilient connective tissue between one body and another. Strands thicken into solid links between the ancient and the modern, utility and self-expression, the digital and the physical, the personal and the political. By exploring the inherent qualities of abject manufactured material, the body binds with other bodies and other places, some known, some not. It is work, but outside the tumultuous dominant economic system. It is an experience of the history of production and distribution through the material at hand. Even in these times, when gathering around a table is a hazardous activity, when our pack species is feeling at loose ends, masked up and reluctantly apart, the tactility of rote hand-making grounds us into the here and now, one stitch, one loop, one knot at a time. We grasp at the tendrils, continuing the work, with the results standing as artifacts of a time, place and our individual and collective states of being. Three major works created over one year remind me of the uncertainty, the panic, the perilousness of these times, and of the solace gained through individual making and the joy of making with others. The three are relics of two years of material research that culminated in a Master of Fine Arts 2020 exhibit set up one day before the university locked down. 1. Scaffolds2. Resurge3. Hearth Day 12 painting: Embroidered details in a scene of a newly "thrashed" hay field. Day 12 painting: Embroidered details in a scene of a newly "thrashed" hay field. I've just returned from a month in the big country of southwest Saskatchewan: big skies, big farming operations, big empty days that were all too much at the start of my artist residency at the Wallace Stegner House. Suddenly agoraphobic, I pulled down all the blinds and paced around that lovely century-old house, wondering what on earth possessed me to throw myself into this imposing patchwork landscape. I am not a landscape painter; that's my dad's bag. Plus I came by plane and an eight-hour car ride, so even if I did want to paint, I didn't have my usual large stretched canvases and totes of paints. I did bring a few of my usual travel essentials: embroidery hoops, needles and floss — and an old bed sheet. I knew there was just a couple of stores in town, and none would be selling art supplies so I packed a tiny travel set of liquid acrylics, a few brushes and a pad of mixed-media cardstock. My sketchy plan involved, well, sketching with my father, who has spent some of every summer in this tiny town of Eastend ever since he filled the Stegner House with his landscape paintings 15 years ago. We were quite a pair: me, not at all comfortable with the whole plein-air tradition, and him, increasingly unfamiliar with his life's work of painting that involved biking into the country to sketch then returning to his basement to paint in the heat of the day. (Actually we were mostly a trio, his wife acting as facilitator for whatever this was, supplying us with water bottles, sunhats, sketch pads and willow charcoal, and generally getting us on the road.) We circled around this vague idea of mine as we circled around this dead-quiet, struggling little town every morning. But the awkwardness turned to anguish back at my studio as I undertook the tedious pursuit of finding some interest — or even the point — in painting puffy clouds and dun-coloured hills. A week later and out of sheer frustration at my lack of landscape-painting prowess, I resorted to dropping diluted paint on a taut scrap of bedsheet in an embroidery hoop just to watch it bleed. I threw the first painted scrap away and did another, with a little more intention, then threw that away too. Within a couple of hours I figured out the right water-to-paint ratio to create a slightly controlled bloom with each stroke. A lot of other distracted behaviour (baking apple crisps, walking by the river, venting via text to my artist friends) meant that each additional stroke was added to a dried layer and by the end of the afternoon, a landscape was emerging on a miniature stretched canvas. That one I didn't throw out. But it was still a little hazy. That's when I thought about using my stash of embroidery floss for final line work. I sat in the cool of the front screened porch that evening and embroidered some more information onto the painting. It was a clumsy first effort but soon I was enjoying the daily practice of biking in the morning with my father, painting something inspired by the ride in the afternoon, then embroidering some details in the evening, inviting others to join me for stitching sessions on the front porch. I did this every day until I had 12 little paintings, each a progression from the last. I saw them as blocks for a future quilt, which led to a well-attended culminating exhibit, "Scenes from a Quilted Landscape." But now I'm viewing them as something beyond a quilt and beyond the horizon. I'm calling them Points of Interest: something to build on and build with. As with all creative pursuits, forcing solutions is futile. My original idea of coaxing my father back into his painting studio by getting him to share some of his process with me was a non-starter. These days he finds everyday joy in the moment, whether that is spotting a hawk while biking the backroads, playing a languid rendition of The Girl from Ipanema on piano in the hot afternoons, or watching the town's many cats on the prowl from the front porch of the Stegner House while his wife and I embroidered the summer evenings away. I'm not sure if he knew it but he passed on to me the most valuable lesson for painting a scene: You have to actually see it. Slide-showing the process: Vancouver-based creative force Omer Arbel and Monte Clark teamed up to embrace the power of happy accidents (Carlyn Yandle photo) Vancouver-based creative force Omer Arbel and Monte Clark teamed up to embrace the power of happy accidents (Carlyn Yandle photo) Last week Monte Clark gave four of us some insight into how an experiment by Omer Arbel went awry and ended up as a dazzling installation in his newish Monte Clark Gallery. The heavy, glittering swags appear as silver-dipped coral or precious Crown hardware retrieved after a palace inferno. The hardened bits of chaos are a dazzling example of why failure is vital in the push for new ideas and materials. "Failure is a constant companion," says Vancouver-based creative force Arbel, in Vancouver Magazine. It was the perfect preface for my '3 artworks a day for five days' challenge that bounced over to me on Facebook. Risk is essential in my work but I don't have Arbel's creative empire to absorb expensive failures, so I turned to stuff lying around the house (a.k.a. Found Domestic Materials) in my thrice-daily experiments. The way I see it, the materials used below were already deemed waste, so if the tests didn't work out, so what? At least no new materials were harmed in the making. Day 2:Day 3:Day 1:Day 4:Day 5:It's getting close to a decade since I packed it all in: my needles and wool, my sewing machine and fabrics, my mid-level-management career. There was more to explore. I've been mixing it up with a wide range of materials (and makers) ever since but even I'm surprised to find that my latest tools of choice for bushwacking new routes of making are the ol' crochet hooks, knitting needles, rug hooks and embroidery needles. The line on the paper has always been too limiting to me; I need to pick up that line, play with it in my hands, turn it into area, then volume. I remain entranced by the possibilities of connecting something created by a silkworm or an industrial manufacturing plant to a mathematical model or a wearable with uncomfortable connotations. The beauty of fiber is in its physical and metaphorical ability to connect the Art side to the Design side (not to mention the science side), weaving the two together until it's clear that playing with ideas cannot be put into separate boxes.  'Spore' (2011) serves as promo visual for the Vancouver design group. 'Spore' (2011) serves as promo visual for the Vancouver design group. Except if we're talking shipping boxes, for the Toronto Design Offsite (TO DO) Festival next month. A few object-experiments from my ongoing Fuzzy Logic series will be packed in there, as part of the Vancouver group of makers, selected by the Dear Human creative studio. It's all part of the ‘Outside the Box’ exhibits featuring works from three selected Canadian cities — Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver — and five from the U.S.: New York, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles and Seattle. It's a fine way to mine local design ideas and visions through an unexpected selection of objects that are shared in various locations via specific-sized shipping boxes. The Vancouver contribution includes nine individuals and teams who live, design and make in the greater Vancouver area. The connecting thread is a pursuit of a design practice through material exploration, according to Dear Human. "Whether through common applications of unusual materials or transcending common materials through unusual applications, exploration is evident in each of the included objects." Rounding out the Vancouver Outside the Box contingent are: Cathy Terepocki, Dahlhaus, Dina Gonzalez Mascaro, Hinterland Designs, Laura McKibbon, Rachael Ashe, and Studio Bup.  Playing with fiber optics (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Playing with fiber optics (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Vancouver Outside the Box will take over the windows at 1082 Queen Street West, Toronto, from January 19-25, 2015. TO DO is an annual city-wide not-for-profit week-long festival that celebrates and showcases the nation's design scene, providing exposure and cross-pollination of ideas and techniques. There are too many exhibits, installations, talks, parties and films to list here, so check out the full (and growing) schedule here as well as the fun promo video.  Detail of Fiber Optics (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Detail of Fiber Optics (Photo by Carlyn Yandle)  Janet Wang plays with the Madonna and Child mainstay. Janet Wang plays with the Madonna and Child mainstay. I spent most of the day yesterday sitting with a very close friend in a hospital bed, waiting for the surgeon to slice into her gut and remove a large cyst and maybe an ovary or two. Or maybe all her lady parts. There was frank talk about the expected pooling blood and lingering pain and there were some last-minute tears as she was wheeled away. It was hardly the time to go mingle at a gallery that night, but friends and family would be there for the opening of the Domestic Interventions show so it was the right thing to do. My sister exhibitors, Monique Motut-Firth and Janet Wang, had probably wrestled with attending too; they were both fending off whatever bad colds their little kids had brought home. But we all showed, and even managed to say a few words about the work.  Monique Motut-Firth: Portrait of the artist Monique Motut-Firth: Portrait of the artist I mention all this because this is what the work is about: trying to nurture an art practice when there is other, more pressing nurturing to be done, not to mention the cleaning and the making-a-living. Sometimes you just have to laugh over the lunacy of trying to paint or build or cut or even think amidst the domestic pressures; sometimes you’re ready to toss it all in, but don’t because you know this ability to express the predicament is what holds you together. That’s why this show includes uneasy domestic objects, uncomfortable self-portraits and sculptures, paper dolls composed of the fictitious feminine form from women’s catalogues. We brought these works together to talk to one another, and to try to convey that dis-ease of the familiar with the strange. There’s something funny about a tiny mother-artist figurine gnawing through the telephone wire or a mannequin wrapped in 1950s ads of ecstatic home-makers or a long line of girdled paper dolls, but there’s a dark side too.  Body of Work, by Carlyn Yandle Body of Work, by Carlyn Yandle We love our families and our home life but we need our art practices too. We may live in a corner of the world that respects cultural workers as much as welfare recipients but we can’t help ourselves. Our domestic world and our work as artists will continue to twist and intertwine and something will continue to emerge that will evoke the messy, conflicted, emotionally charged and banal everyday. And that’s important. *** Domestic Interventions, curated by Jo Dunlop, runs from Oct. 17 to Nov. 15 at Cityscape Community Arts Space gallery, 335 Lonsdale Ave., North Vancouver (three blocks from Seabus terminal). Hours: Mon-Wed, Fri. – 9 am-5 pm, Thursdays 9 am–8 pm, Saturday noon-5 pm.  My brief stint as a home organizer was an eye-opener — door opener, to be precise. I got a rare view of the reality behind the doors of some beautiful houses. Often I was the only outsider who had been invited inside for years, for many different reasons. Home is where it all hangs out, for better or for worse. Ostensibly it’s where the meals and love and traditions are shared but it’s also the backdrop to power struggles or social isolation (by choice or by circumstance) and other domestic dynamics that we don’t post or tweet or share or Like. It’s why Monique Motut-Firth, Janet Wang and I decided that our group exhibit at Cityscape Community Art Space opening next week should include an opportunity for others to take a break from the relentless perfect-homelife-branding and share in the real, in our Dirty Laundry installation. During the course of the month-long Domestic Interventions exhibit visitors to the North Vancouver gallery will have the option of anonymously adding one of their own pieces of domestic reality to the ‘laundry line’ set up in the Lonsdale Avenue space. It could reveal that our very private, personal problem might actually be a public issue that deserves an airing. Or it may be that no one will take on the option. There’s power in negative space too. *** Domestic Interventions, curated by Jo Dunlop, runs from Oct. 17 to Nov. 15 with an opening reception Thursday Oct. 16, 7–9 pm at 335 Lonsdale Ave., North Vancouver (three blocks from Seabus terminal). Hours: Mon-Wed, Fri. – 9 am-5 pm, Thursdays 9 am–8 pm, Saturday noon-5 pm. |

browse by topic:

All

Archives

October 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed