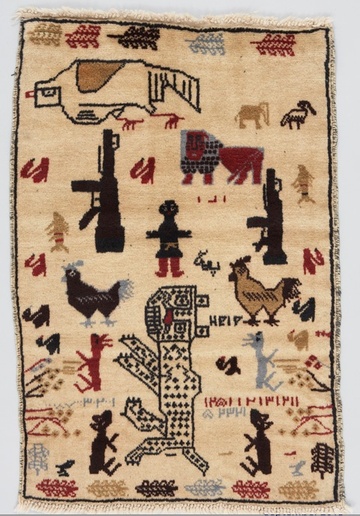

I became acutely aware that craft can pack a serious political punch when I first saw a fleeting image of an Afghan rug designed with bombs, grenades and exploding figures, created by children.

It's a potent example of how craft can transcend its place from a use/decorative object to an art object, and was just one of many collected war rugs that formed a 2008-2009 exhibit at the Textile Museum of Canada.

It is their inappropriateness, in conventional terms, that resonates. And even if the maker is never known, his (or more likely 'her') soul is woven into the piece. The expression is a response to the maker's environment, providing moments of discovery while posing new questions, like: What is the use of a rug as a comfort object if it's communicating discomfort?

It's why rags can become collectors' items, like this Japanese 'boro' (literally 'rag') futon cover that appears on a collectors' website (and at collector's price of $1850.US)

While there's no apparent narrative in this humble textile, it speaks of the time when it was made, in the form of a visual sample of the fabrics of the day. It's also a visual history of sashiko stitching, which evolved from a method of repairing and recycling fabrics to a highly symbolic craft. And it speaks of a sensibility toward thrift, whether out of simple necessity or attachment to the materials (probably both).

The transcendent ability of crafts is seen in how simple stitchery evolves, from patching a jacket to emblematic artworks.

Those patterns may reflect the actual rural culture or physical surroundings, or a nostalgic yearning of place by the maker.

Cranes are part of my place that during my life is enduring massive change as my place transforms from industrial port town to glittering international resort city.

Where is it all going? I wonder that every day as I dodge the bike route closures and count the clusters of looming cranes pivoting overhead in an aerial Developers' Dance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed