Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

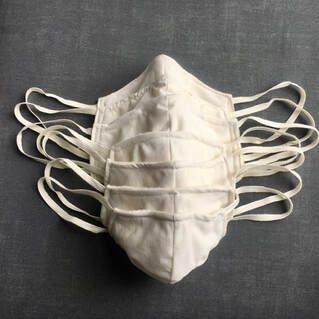

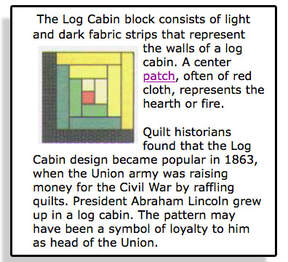

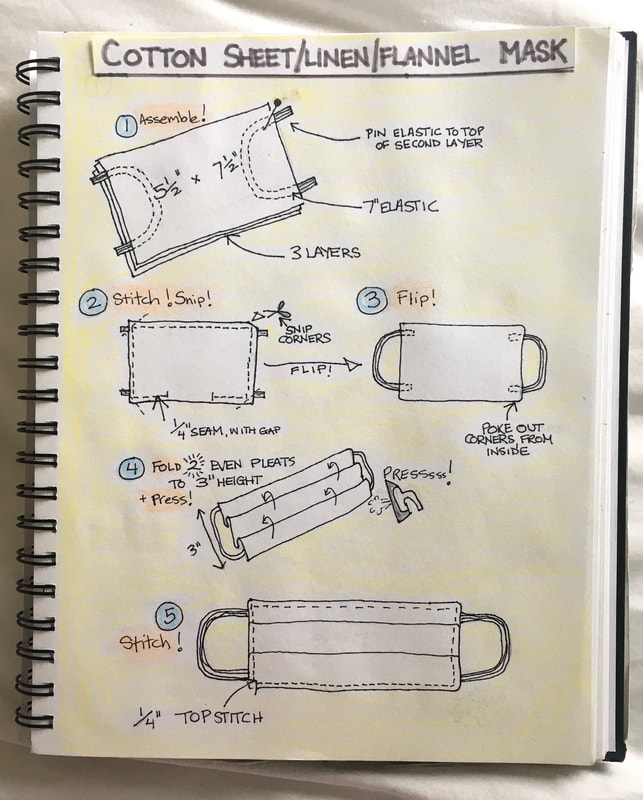

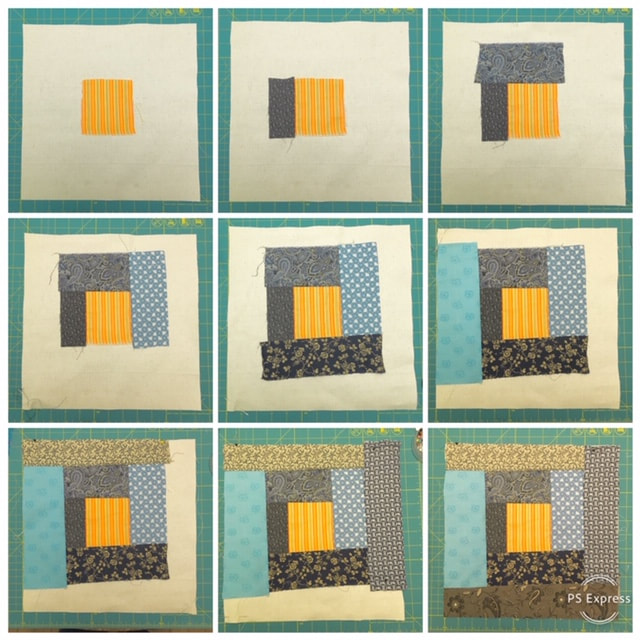

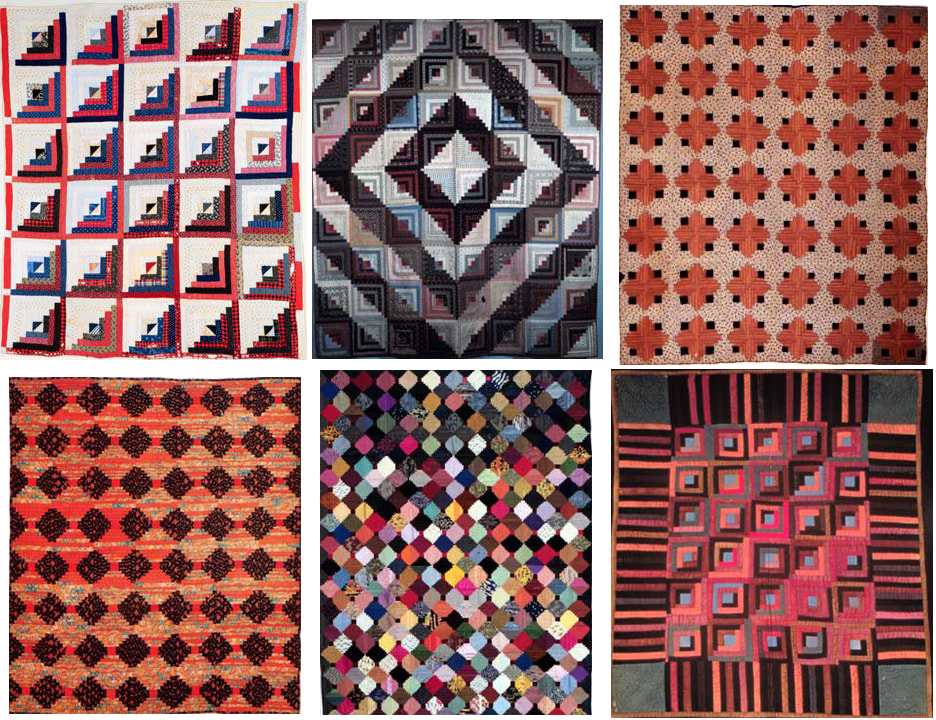

We who turn to rote hand-making activity to quell our anxiety have been knitting, sewing, embroidering, crocheting and needleworking up a storm. My go-to, like countless others stuck at home, is making masks. As the death tolls roll in, I am on auto-pilot.  The thing about busying the hands with tiny repetitive motions is that it opens up time to think, to reflect on the incoming: the unfathomable graphs, reports, studies and scandals. What I’ve been reflecting on as I rotary-cut those squares of cloth, feed them into the machine and steam-press in the pleats is the great homemade-mask debate: to wear or not to wear. To that question I have no doubt: it’s a hard ‘wear’ if you are in the vicinity of others. Sure, there is a tsunami of science that proves that the three-layered, tight-weave cotton reusable mask that I’ve been making won’t protect you — the wearer — from catching the virus but this is not about you and you alone. This is about us, about keeping our own damn germs to ourselves, a civic duty seen in east Asian nations that have been-there-done-that with SARS. As pointed out in today’s (at this writing) article in The Atlantic, a store full of shoppers in masks may be seen by those on this side of the Pacific Rim as a sign of the coming apocalypse but one of assurance on the other side: I’ll protect you if you protect me (Check out #masks4all and #youprotectmeIprotectyou). At Emily Carr University of Art + Design, where I’ve spent the last two years, masks suddenly appeared on some student faces as Covid-19 hit the news, far before any social-distancing policies were set. My personal observation is that those taking these early precautions were likely international students from Asian countries where mask-wearing is a norm for anyone contending with even a cold or seasonal allergies. The sudden sight of all these masks in class and corridors may have unsettled the rest of the student body but it inspired me to design something I’d like to wear: reusable, washable, of natural felted fibre, sculpted so it didn’t touch my mouth, infused with my favourite “Panic Button” essential oil blend.  I wasn’t always cool with milling around with the masked ones. When I landed in Japan for what would be an 18-month stay in the late-’80s my first snapshots were of all kinds of people in masks in Kyoto, from little kids in black uniforms on their way to school, to teens picnicking under the blooming cherry trees to old ladies in the narrow streets of Gion. I came to appreciate all the masks worn while cheek to jowl in the infamous Midosuji subway in Osaka, starting with the official charged with gently pushing the commuters into the cars. Reflecting on this (now, while I sew), I wonder what those socially-responsible commuters must have thought about being stuck up against these gaping, mouth-breathing, sniffling foreigners. I’m reflecting on the real, insatiable need for masks in my own vicinity, right now, for those who are jammed into shelters and squalid hotel rooms with shared bathrooms. While I await reports on how this pandemic is hitting the sick and homeless, I’ll assume masks are a basic need. And until I am tested, I’ll assume that I am an asymptomatic carrier. I mask up for your protection when I go out for my essential business and when I return I disinfect it, put it back in its baggie, then get back to the task at hand. See my simple three-ply pleated pattern below, or, for you non-sewcialists, check out the T-shirt version at bottom. I have this idea for building healthy community in this pretty/cold city through hand-making. It’s a process of making peace with ourselves and connecting with others, transforming individualized desires (thanks, capitalism) into shared desires for a sustainable life and world.  Vancouver artist Jenn Skillen — collaborator No. 1 — beta-tests a freeform, no-measure hand-stitched log cabin block method. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Vancouver artist Jenn Skillen — collaborator No. 1 — beta-tests a freeform, no-measure hand-stitched log cabin block method. (Carlyn Yandle photo) That's the idea. 'How' is the big question. I start with a few rules of thumb. (I love that phrase for its controversial origin that is a deep-dive into human history and etymology, but also for the visual of the hand-as-tool.) First, the activity must be low-barrier enough to open it up to as much collaboration as possible — no need for special skills or equipment or fees or even shared verbal language. Second, the project must use only found material: freely available, with no better use (because there's already too much stuff in the world). Third, the project must spark interest, otherwise, why would people bother? A decade ago, these rules of thumb resulted in The Network, an ever-growing public fibre-art piece engaging a wide variety of folks around Vancouver, co-created by Debbie Westergaard Tuepah. That knotty piece continues to weave through my work, mummifying a perfectly good painting practice, winding around ideas of alternative space-making, shelter, and safety nets. Now it's needling into my current project: the Safe Supply collaborative quilt. 'Safe supply' were the two words on the lips of the crowd at a CBC Town Hall gathering two months ago. Providing a safe supply of opioids would go a long way to addressing all the problems and fears raised by everyone from student activists to local businesses, from concerned politicians and developers to Indigenous elders: the toxic-drug death epidemic, violence, homelessness, sexual exploitation, theft, vandalism, mental illness. A safe supply is inherent in the view of addiction as a public health issue, not an individual, moral failing.  'Kettling' homeless people into Oppenheimer Park has resulted in a colourful display of a national humanitarian crisis. (Carlyn Yandle photo) 'Kettling' homeless people into Oppenheimer Park has resulted in a colourful display of a national humanitarian crisis. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Ground zero of this humanitarian crisis is the colourful, chaotic tent city crowded in Oppenheimer Park straddling Chinatown and the old Japantown. The sight of all those bright, tenuous shelters layer up with this history of racism and injustice, stolen land and lives, and soon I am binding up ideas of found colourful material and that call for Safe supply!, embedding it all in a design, with designs for this as a group project destined for exhibit in more privileged spaces. It is planned as a comforting activity in this often ruthless, discomforting city: a dis-comforter.  Historical clipping from the llinois State Museum website reveals the log cabin quilt has ties to ending slavery. Historical clipping from the llinois State Museum website reveals the log cabin quilt has ties to ending slavery. I begin this overarching theme one block at a time, and that block is, fittingly, the traditional 'log cabin.' There's a long history of the log cabin block, ingenious for its simple construction that makes use of even the smallest, thinnest available scraps as well as its history as a vehicle for social justice. I am attracted to the name that stands as aspiration for home and all that that entails, beginning with the hearth, the centre of the block. From the hearth, the block is built in a spiral of connected scraps to form a foundation for countless quilt designs (traditional examples below). The work has not yet begun but like all collaborations it begins with faith in people and trust in my practice. Something will emerge. We will engage. We will generate some heat in this log-cabin community. Some useful how-tos and overall pattern examples: Back when I was still transitioning from workaday newspaper editor to mainly work-for-free artist I applied for a Nexus card. "Whaddaya you do for a living?" asks the clerk in her American drawl, without looking at me. When I get this question I always wish there was an easy answer, some simple keystroke like in the relationship status options on Facebook. "It's complicated," I say. She sighs. I start in about how I was a journalist but then quit to go into full-time Fine Arts studies, then after graduation I got a studio and am now developing an art practice and doing work for upcoming projects... and stop as her eyes fall to half-mast. We go back and forth for a while like this when she announces: "I'm gonna put you down as housewife." Even though I've always been self-supporting I decide not to waste my breath defending my non-conforming life choices. But really, I'm using the best skills I have to be a contributing member of society and I'm grateful to be a part of the ever-expanding, borderless community of crafters, craftivists and visual artists, all connected beyond language by hand-making for peace of mind and social, political connection. Craft creates wellness, it brings humanity during turbulent times, it breaks down hierarchies and is the connecting thread between those who make for personal, tactile pleasure or for use and those who make art for art's sake. Craft is as at home in the home as it is on Etsy or in the white-cube gallery. It has footholds in ancient practices and the avant-garde. It complicates categorization and won't be fenced in (or out).

Making and their makers form an essential humanizing force more encompassing and enduring than even advanced capitalism but there's no way to show that value on a Nexus form.

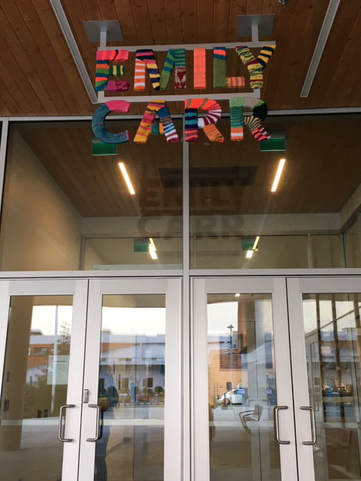

I reject that line of questioning. And I am not married to a house.  The other day I did this because it really needed to happen. All that gleaming new-campus architecture, surrounded by other gleaming buildings and gleaming buildings yet-to-come was begging for a little fuzzying up. I did my undergrad at the old Emily Carr University of Art and Design campus which was decidedly less smooth and metallic and more crafty, situated as it was in the Granville Island artisan mecca on the ocean's edge. I liked running my hand along the old wooden posts carved with decades of scrawled text, and all the wiring and ductwork that in the last few years looked like a set out of Brazil. I miss the giant murals on the cement factory silos next door and the funky houseboats and the food stalls in the public market and Opus Art Supplies 30 feet away from the front entrance. The new serene, clean Emily Carr building is surrounded by new and planned condos that most students could never afford, high-tech companies and, soon, an elevated rapid transit rail line. As much as I wanted to return for graduate studies, I was not convinced that I would be a good fit here, so asking for permission and access to the sign was a bit of a trial balloon for me. I got quick and full support for the idea and its installation, and now see this new white space as a blank canvas, ready for the next era of student artistic expression. This is my first solo yarn-bombing foray. A bunch of us attacked the old school back in the day for a textile-themed student show but I have yet to meet my people here. So the Emily Carr Cozy is not just a balloon, it's a flare. Is there anybody out there? As I busied my freezing fingers with the stringy stuff (in hard hat, on the Skyjack operated by design tech services maestro Brian) I kept an ear out for reaction. And it was good. Sharing the fuzzy intervention on social media (#craftivism, #subversivestitch etc.) reminds me that I am not alone in my need for needling authority. Indeed, this public performance includes behind-the-scenes connecting with my community of makers to collect their leftover yarn and thrift-store finds even before the main act. (You know who you are.) Textile interventions in the public sphere have a way of provoking polarizing responses. Some love the often-chaotic hand-wrapping of colourful fiber; others view the crafty messing with architecture with disdain of all things cozy and crafty and engendered female. I liked the idea of having to wear a hard hat and working for four hours in a Skyjack, in the mode of construction workers in the immediate vicinity of my rapidly changing hometown, to complete my knitting job. A visual of the process, below. (All photos by Caitlin Eakins)  MORE THAN DECORATION: Flower images carry deep cultural significance for the Maya. Left: A figure dating from 600-900bc nestled in a lily. Centre: Needlepoint detail from a huipil (top), part of a traditional everyday dress. Right: Jesus emerging from a lily in an oil painting of the Immaculate Conception. Carlyn Yandle photos I've made it my mission to shake things up by injecting the handmade domestic — doilies, quilts, sweaters and rugs — into austere, authoritative spaces and places, from pristine galleries to sketchy undersides of my city, pushing back on everyday misogynistic descriptors like 'girly' or 'old-lady' or the slightly derogatory 'frou-frou' and 'flowery.' Then I landed in Merida, Mexico, last week where there is no fight against things flowery and archetypical feminine. Here in the capital of the Yucatan state and the ancient Maya culture (not dead but flourishing against all odds, by the way, like Canada's indigenous people) the streets are a flowery visual field of richly needleworked garments and handmade decorative traditions woven throughout the city, from tiled floors to architectural details and murals. Above and far right: Carpet-like ceramic tile floor artworks are more than decorative. At left, a four-petal flower signifies universal realms; Centre: Merida's impressive El Gran Museo Del Mundo Maya pays tribute to the importance of the handmade floral motif in one of its exhibit salons. Carlyn Yandle photos Flowers are so sacred and symbolic in the highly complex Maya culture that the Franciscan missionaries, in service of the Catholic Church, appropriated specific flower designs in their battle for their souls, in a cultural war of the roses (and lilies and other healing, spiritually-weighty blooms). Coming from the land of yoga pants, I'm fascinated by this idea that an acceptable form of everyday dress is one's own hand-stitched art piece in the form of brightly-coloured cultural patterns of flowers on white cotton or linen tops and tunics, over an underskirt edged in a thick band of white lace.

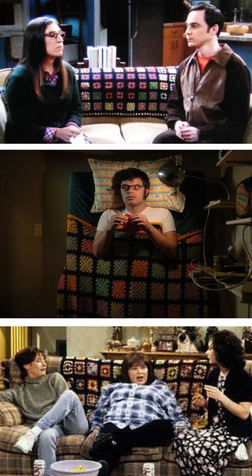

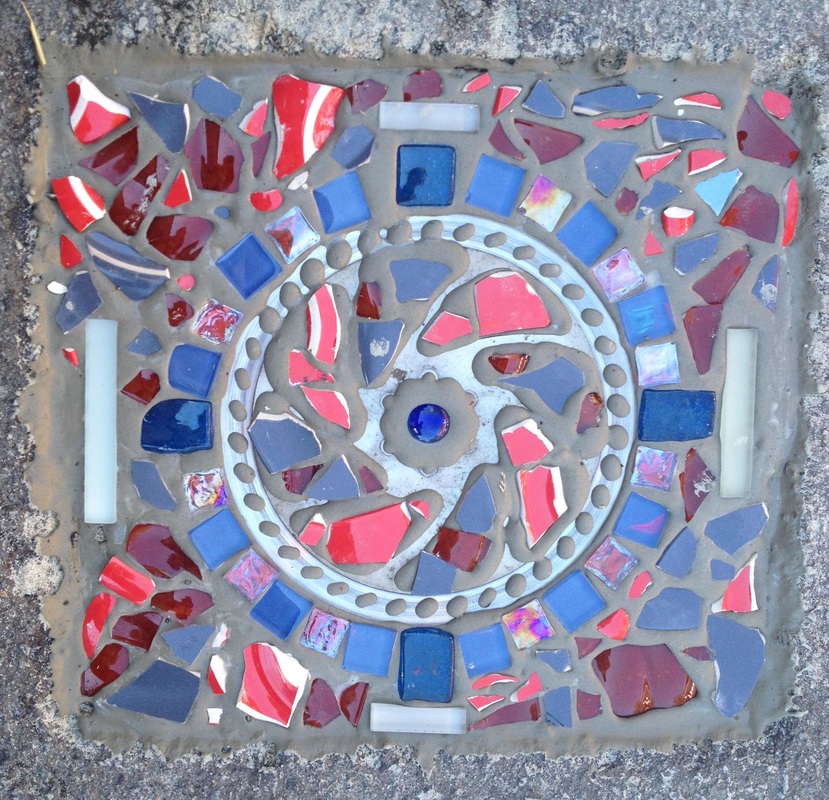

No made-in-China. No apologies, no fading away.  I'm sure I didn't come up with the term 'mosaic tagging' but the idea of embedding found remnants of domestic culture into the built landscape has been rolling around my brain for a while. It finally happened this summer, in an East Van back lane. In the space of one (hot!) half-day, the tiny tarmac'd alley was transformed into someplace special, as neighbours turned found colourful shards of china and pottery into mosaic-ed markers of their home and family. With a plan in place weeks before, each household thought about a particular design (or not — serendipity works too) and collected chipped china dishes, old toys, and mementoes, the whole endeavour of collecting pieces becoming a conversation piece itself among neighbours. The day before tagging day, someone from each household used chalk to draw a shape of their choice for their mosaic and some of the handier people carved out the layer of tarmac by tracing the chalk lines with a jigsaw. As night fell, the sound of smashing plates could be heard. On the morning of the laneway intervention, kids helped stir up cement mix and water, and everyone got busy inserting their bits and pieces into the concrete and touring the lane to watch their neighbours' progress. I love the thought that these upcycled bright bits of pottery and china have created sweet little urban interventions in all that grey tarmac that will withstand our soggy seasons and be around long after the kids grow up and the families move away. It's the kind of project that would never get permission, but the city is forgiving when it comes to community-building. In fact, the block party that night was funded by a small neighbourhood grant from the Vancouver Foundation just for that purpose. Mission accomplished. The mosaic tags remain there as emblems to those families, this time and place, and that one connective neighbourhood event — well, until the developers win. When the white RCMP SUV was spotted cruising around the Maple Street section of the community gardens early Monday morning, it was clear that the chainsaws and earth-movers were next.  Placeholders for levelled gardens: Wrap I and Wrap II, 10' diameter each, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Placeholders for levelled gardens: Wrap I and Wrap II, 10' diameter each, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) For the next three days all the gardeners of those little plots along the Arbutus rail corridor could do was ask that some of the uprooted shrubs be saved. But mostly those who had the stomach to watch the carnage were shaking their heads, hugging one another, trying not to cry. The train used to come by here when there were gardens. Now there is no need for trains yet all but a fringe of the gardens must go. It's the futility of the destruction of people's source of food, pleasure and community that hurts the most. CP has every right to their right of way, but it's a crying shame all the same.  Backhoe tracks and Wrap I, 10' diameter, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Backhoe tracks and Wrap I, 10' diameter, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) When all was left was the tracks of the backhoe, I thought that laying down some giant doilies seemed appropriate. Or at least it didn't seem any more ridiculous than levelling the gardens along a useless spur where the rails have long disappeared under the tarmac of some streets it used to cross. There was no one around when I unfurled the two 10-foot-wide doilies on the bare dirt after the land-clearers left for the day - eerie for a time and place where there's usually all sorts of people tending their vegetables, walking dogs, riding bikes, pushing strollers or just surveying the spring coming on. But soon a few curious souls ventured in to ask what I was doing or snap some Instagram-destined pics. Conversations started up, mostly about Those Assholes but also about the grandmothers who loved their doilies, or the other things that these things reminded them of. A bit of absurdity in the face of absurdity, but it kick-started something. When one's world seems unbearable "it is the sublime madness that makes one sing," Pulitzer-prize-winning war correspondent/author/minister Chris Hedges told the crowd at a packed downtown church two weeks ago. Acts of creative expression in the face of devastation are signs of a belief in a "divine justice." They are small acts of hope that say, 'We exist.' Hedges rocks your world view here (talk begins at 16-minute mark):  Maybe it's the chilly monochromatic climate at work here, but I'm suddenly wrapping myself up granny squares. The more I think about them, the more potential I see. There's a lot of culture woven into those fuzzy little colour grids. They're there in the background of popular culture, infusing irony and cozy home-yness, nostalgia and disdain. One graces the couches of neuroscientist Amy Farrah Fowler's nerdy apartment and Roseanne's working-class house. Jemaine sleeps under one (badly). Sure, they achieve that soupçon of shabbiness or tastelessness essential to the story but those set decorators are no idiots; granny squares inject hits of high colour and pattern to the visual field. They are trippy, decorative non-decor objects. Their form is used because of their assumed function over form.  They are the throws that are thrown around, their colourful geometry reflected and refracted so that they radiate western domestic culture, love it or hate it. Cate Blanchett adorned a designer version on the red carpet, to a chorus of derision by the fashion police, which secured the actress more publicity. There's something delicious in the mix between haute couture and the easy, scrappy crochet method that results in over 13,000 Etsy items under the search term, "granny squares". I've loved/hated granny squares ever since my cousin and I were given matching shrink vests at age 10, from our moms. I would have been wearing that single, large purple granny square at a time when the Italian dads in the neighbourhood were setting up that granny-square pattern in concrete breeze walls around their brand new Vancouver Specials.  One breeze wall in a photo essay by the author of joy-n-wonder.blogspot.ca One breeze wall in a photo essay by the author of joy-n-wonder.blogspot.ca Like the blankets, the breeze walls evoke utility and thrift but are visually interesting enough to warrant new consideration. The modularity of granny squares and breeze-wall blocks ooze with potential, especially as a mash-up. Granny squares command attention. The Los Angeles Craft and Folk Art Museum took on new dimensions when it was covered in thousands of donated granny squares as part of its CAFAM Granny Squared installation a couple of years ago.  Suddenly, a city that is generally at odds with notions of the handmade, the domestic and the artisanal was attracting mainstream media attention for its collaborative crocheted culture jam. A couple of years before that, in 2011, members of many Finnish women's organizations and the craft teachers' union blanketed Helsinki Cathedral's steps in 3,800 granny square tilkkupeitosta (Finnish for 'quilt').  The modular motif marries beautifully to existing architecture, as the granny squares take on a Tetris effect, cascading down to the giant public square in this domestic intervention. But what about the granny square as a building block itself? What if a building appeared to rise out of a giant crocheted coverlet? How could concretized crocheted granny squares be utilized as sculpture? It's a fuzzy concept worth building on.  (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) What do you do when you're suddenly confronted by a threatening sign where this year's crop of wild blackberries were leveled along the Arbutus corridor? You yarn-bomb it, of course. That's what one craftivist did, and it's lovely too: a raspberry sheath with fuzzy stripes, jaunty buttons and a bowtie. It says, Sorry officer but we can't take you seriously in that ridiculous outfit. It was a charming, disarming move following the brutal behaviour of the railway bosses who are in the midst of strong-arming the City to pay big (starting with smashing through a few gardens, like a gangster might start by hacking off a toe). On the midsummer's day of the clearcut, a little old lady in her walker stared at the spectacle and said in a shaky voice, "I'm heartbroken." The raspberry sheath is a humorous act but the dedication to the making reflects on the maker's serious intention. This piece of visual satire is a daily reminder to question authority. Two months later, this act of self-expression remains intact — knitted fiber is durable that way. Indeed, 'use' is never far away from craftivism. Anyone who bikes hither and yon in this town has seen yarnbombing and other furtive fiber-based forms. it's almost a call-out to likeminded makers to mobilize, like the bat signal. And there's just the place to hang out and plot the revolution next week in the radical hotbed of Mount Pleasant.  (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Make Your Voice Heard: The Intersection of Craft, Creativity, & Activism is a dangerous mix of accomplished crafty authors and alcohol served up at Hot Art Wet City gallery, Tuesday Oct. 7, 7:30pm on. Authors Kim Piper Werker, Leanne Prain, and, all the way from Arlington, Virginia, Betsy Greer will each speak about creativity and do some book signings. From the Hot Art Wet City site: Kim Piper Werker is the author of Make It Mighty Ugly: Exercises and Advice for Getting Creative Even When It Ain’t Pretty and several crochet books. Kim teaches hands-on and discussion based Mighty Ugly workshops and lecture-conversations that help people build confidence in what they make and do. Leanne Prain‘s newest book is Strange Material: Storytelling Through Textiles. A professional graphic designer, Leanne holds degrees in creative writing, art history, and publishing. Betsy Greer is a writer, maker, and researcher and the author of Craftivism: The Art and Craft of Activism. She runs the blog Craftivism.com and believes that creativity and positive activism can save not only the soul, but also the world. |

Sharing on the creative process in long-form writing feels like dog-paddling against the tsunami of disinformation, bots, scams, pernicious sell sites and other random crap that is the internet of today. But I miss that jolt of inspiration from artists sharing their work, ideas and related experiences in personal, non-marketing blogs, so I'm doing my part.

browse by topic:

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed