Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

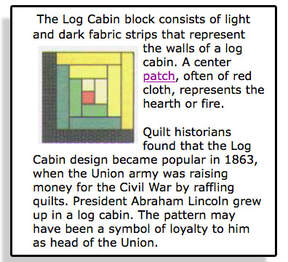

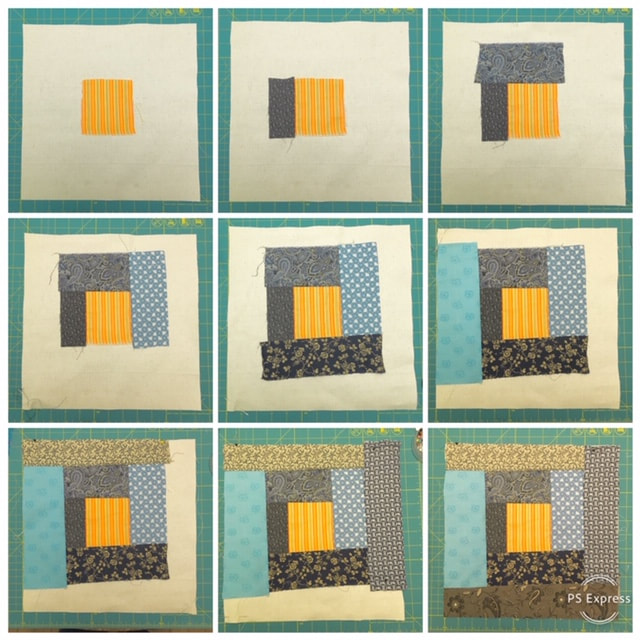

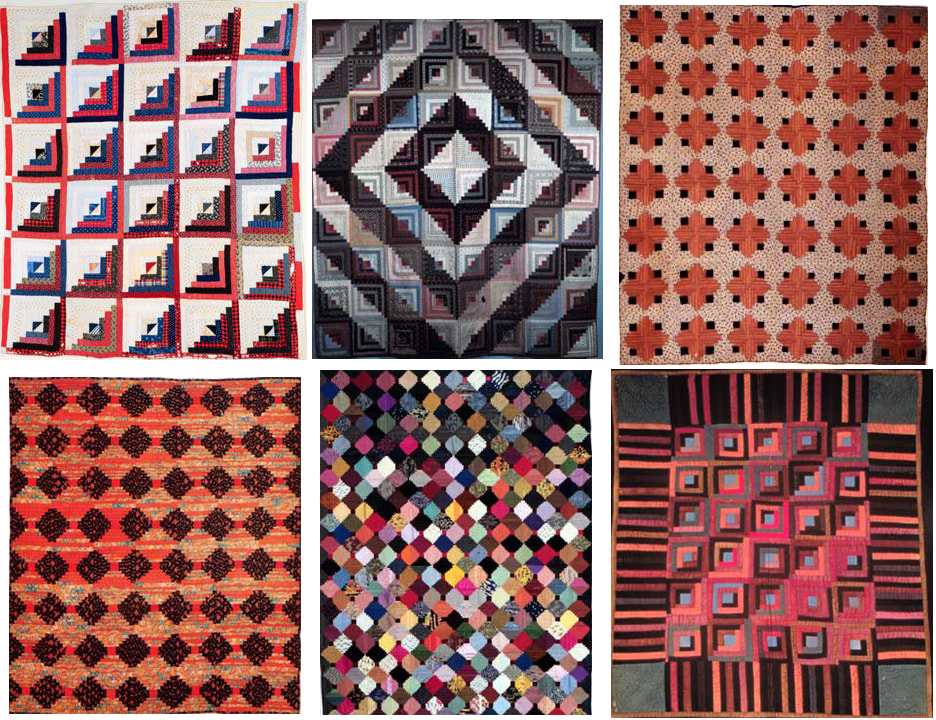

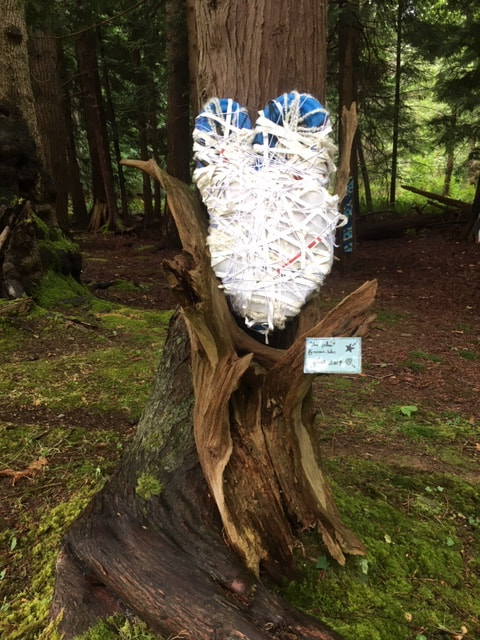

I have this idea for building healthy community in this pretty/cold city through hand-making. It’s a process of making peace with ourselves and connecting with others, transforming individualized desires (thanks, capitalism) into shared desires for a sustainable life and world.  Vancouver artist Jenn Skillen — collaborator No. 1 — beta-tests a freeform, no-measure hand-stitched log cabin block method. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Vancouver artist Jenn Skillen — collaborator No. 1 — beta-tests a freeform, no-measure hand-stitched log cabin block method. (Carlyn Yandle photo) That's the idea. 'How' is the big question. I start with a few rules of thumb. (I love that phrase for its controversial origin that is a deep-dive into human history and etymology, but also for the visual of the hand-as-tool.) First, the activity must be low-barrier enough to open it up to as much collaboration as possible — no need for special skills or equipment or fees or even shared verbal language. Second, the project must use only found material: freely available, with no better use (because there's already too much stuff in the world). Third, the project must spark interest, otherwise, why would people bother? A decade ago, these rules of thumb resulted in The Network, an ever-growing public fibre-art piece engaging a wide variety of folks around Vancouver, co-created by Debbie Westergaard Tuepah. That knotty piece continues to weave through my work, mummifying a perfectly good painting practice, winding around ideas of alternative space-making, shelter, and safety nets. Now it's needling into my current project: the Safe Supply collaborative quilt. 'Safe supply' were the two words on the lips of the crowd at a CBC Town Hall gathering two months ago. Providing a safe supply of opioids would go a long way to addressing all the problems and fears raised by everyone from student activists to local businesses, from concerned politicians and developers to Indigenous elders: the toxic-drug death epidemic, violence, homelessness, sexual exploitation, theft, vandalism, mental illness. A safe supply is inherent in the view of addiction as a public health issue, not an individual, moral failing.  'Kettling' homeless people into Oppenheimer Park has resulted in a colourful display of a national humanitarian crisis. (Carlyn Yandle photo) 'Kettling' homeless people into Oppenheimer Park has resulted in a colourful display of a national humanitarian crisis. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Ground zero of this humanitarian crisis is the colourful, chaotic tent city crowded in Oppenheimer Park straddling Chinatown and the old Japantown. The sight of all those bright, tenuous shelters layer up with this history of racism and injustice, stolen land and lives, and soon I am binding up ideas of found colourful material and that call for Safe supply!, embedding it all in a design, with designs for this as a group project destined for exhibit in more privileged spaces. It is planned as a comforting activity in this often ruthless, discomforting city: a dis-comforter.  Historical clipping from the llinois State Museum website reveals the log cabin quilt has ties to ending slavery. Historical clipping from the llinois State Museum website reveals the log cabin quilt has ties to ending slavery. I begin this overarching theme one block at a time, and that block is, fittingly, the traditional 'log cabin.' There's a long history of the log cabin block, ingenious for its simple construction that makes use of even the smallest, thinnest available scraps as well as its history as a vehicle for social justice. I am attracted to the name that stands as aspiration for home and all that that entails, beginning with the hearth, the centre of the block. From the hearth, the block is built in a spiral of connected scraps to form a foundation for countless quilt designs (traditional examples below). The work has not yet begun but like all collaborations it begins with faith in people and trust in my practice. Something will emerge. We will engage. We will generate some heat in this log-cabin community. Some useful how-tos and overall pattern examples: Everyone is feeling that relentless creep of plastic that is threatening to consume us, the consumers. I felt myself drowning in the tsunami of stuff over this past year of grad studies at Emily Carr University. Art, as one instructor stated, is a wasteful business. Even as I retreated back to my green, pristine Gulf Island I was hit with it at the end of the long drive through forest to the local dump: a mountain of garbage. This, from a small off-grid community known for its environmental consciousness. My art practice is driven by a need to physically grapple with the unfathomable when words are not enough. In the strange way that an idea for an artwork takes hold, that sight of that mountain of petroleum-derived recycling-rejects led to my latest project: Foundlings. For a while I’d been trying to land on a low-barrier, low-skill technique that could involve kids in the making of objects from found, non-recyclable and non-biodegradable materials. Then I landed on the work of late American sculptor Judith Scott, whose many exhibitions of her curious bound and woven fiber/found objects have led to discourse on “outsider” art, disability (she was profoundly deaf, non-verbal, and had severe Down’s Syndrome), intention, new sculpture forms and the privileged art world. Within a month of escaping the art institution I was driving a pickup-truckload of colourful non-recyclable, non-biodegradable bits from the home-grown garbage mountain to the island’s only elementary school. Before we got to the making part I sat down with the students and shared some images of Scott’s work for inspiration. We talked about how this artist’s method of wrapping, binding and weaving fibre around objects adds curiosity to what is on the inside. We talked about how working with familiar objects and materials in unusual ways can lead to new ideas. And we talked about how an object can be terrible and beautiful at the same time, does not have to be a recognizable thing nor have utility. We worked over time on the pieces, some kids on their own and some in groups of two or three, adding even more fibre and found plastic detritus from their year-end trip to the local provincial marine park. On the final day of school I arrived to pick up the final pieces and was astounded at the creations. They were richly textured, humorous and foreboding, and proof of why I collaborate with children: they consistently demonstrate the importance of letting hands and imaginations fly.

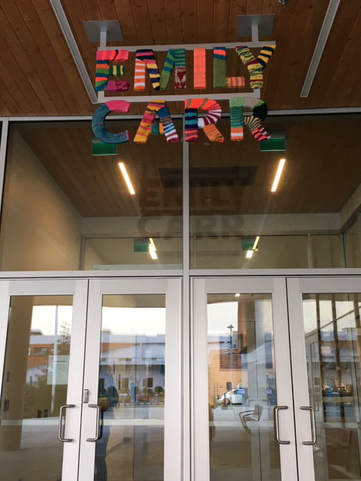

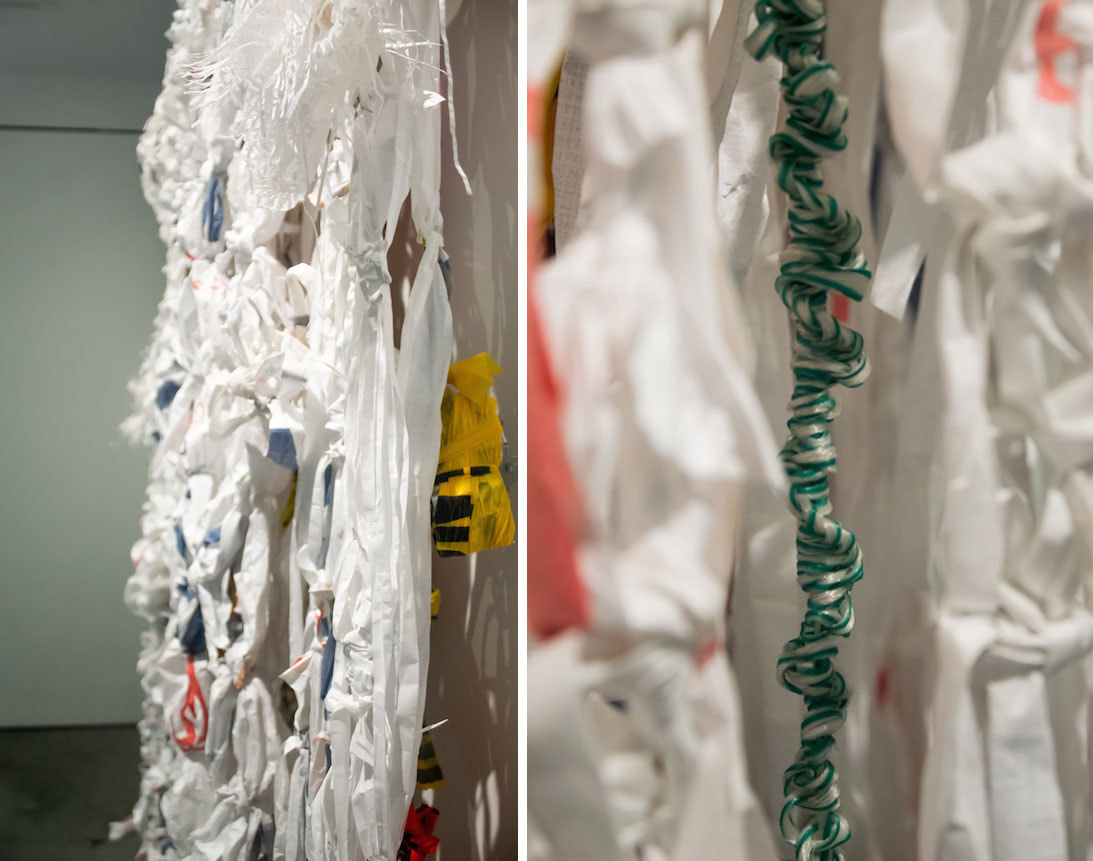

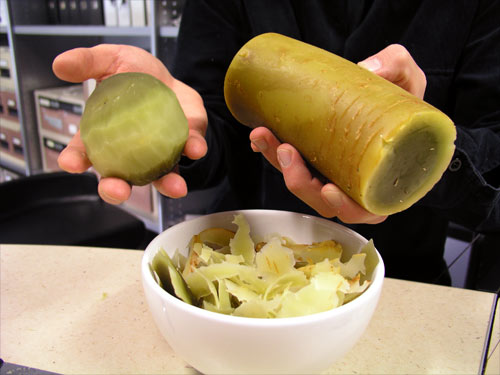

They each titled their pieces in their own hand and I installed them for exhibit on forest plinths (moss-covered stumps from the last big clearcut) in time for the annual Arts Fest. With no chance they’ll degrade in the weather they remain there, pretty and pretty disturbing: our inescapable stuff. The brilliant part about being an aging female is your growing self-acceptance. Maybe this is because you don't feel that ever-present gaze anymore so you’re not feeling as judged. Or maybe it’s because you’ve just had enough of all that and it’s tiresome and dammit you like to be cozy so screw them. Part of my self-acceptance is stepping out of the ‘should-storm’ of art-making and doing what I love to do with my hands: hunting down materials that have already had their first use and playing up their inherent qualities through knotting, weaving, tying, stitching and binding. I want to work repetitively, easily, without technological assistance and without haste or waste. And in doing so I’m carving out space and time to calm down, reflect and to think deeper — more crucial as the distractions threaten to take over.  Nate Yandle photo Nate Yandle photo In this way the work is not just in the form or connotations but the well-being and challenge that is relatable to makers who may or may not self-identify as artists. Wrapped up in there are issues of endurance, innovation, history of labour, the learning of the skill, dedication (and frustration), the specific culture and history of the method, the muscle memory that extends back to childhood, and the relationships built through the gathering of the materials. Through this making I make some hay over the established boundaries between the privileged art world and real life, between craft and sculpture, between tactile and political action. Scaffolds is composed of found spun-polyester building wrap, tarp and nylon cord over an armature of waste construction materials including caution tape, PVC piping, rebar, conduit, baling wire, and junction boxes, all attached through simple knots. Special thanks goes to the construction workers who delivered these materials from their many jobsites to my studio for my useless work with many functions.  The other day I did this because it really needed to happen. All that gleaming new-campus architecture, surrounded by other gleaming buildings and gleaming buildings yet-to-come was begging for a little fuzzying up. I did my undergrad at the old Emily Carr University of Art and Design campus which was decidedly less smooth and metallic and more crafty, situated as it was in the Granville Island artisan mecca on the ocean's edge. I liked running my hand along the old wooden posts carved with decades of scrawled text, and all the wiring and ductwork that in the last few years looked like a set out of Brazil. I miss the giant murals on the cement factory silos next door and the funky houseboats and the food stalls in the public market and Opus Art Supplies 30 feet away from the front entrance. The new serene, clean Emily Carr building is surrounded by new and planned condos that most students could never afford, high-tech companies and, soon, an elevated rapid transit rail line. As much as I wanted to return for graduate studies, I was not convinced that I would be a good fit here, so asking for permission and access to the sign was a bit of a trial balloon for me. I got quick and full support for the idea and its installation, and now see this new white space as a blank canvas, ready for the next era of student artistic expression. This is my first solo yarn-bombing foray. A bunch of us attacked the old school back in the day for a textile-themed student show but I have yet to meet my people here. So the Emily Carr Cozy is not just a balloon, it's a flare. Is there anybody out there? As I busied my freezing fingers with the stringy stuff (in hard hat, on the Skyjack operated by design tech services maestro Brian) I kept an ear out for reaction. And it was good. Sharing the fuzzy intervention on social media (#craftivism, #subversivestitch etc.) reminds me that I am not alone in my need for needling authority. Indeed, this public performance includes behind-the-scenes connecting with my community of makers to collect their leftover yarn and thrift-store finds even before the main act. (You know who you are.) Textile interventions in the public sphere have a way of provoking polarizing responses. Some love the often-chaotic hand-wrapping of colourful fiber; others view the crafty messing with architecture with disdain of all things cozy and crafty and engendered female. I liked the idea of having to wear a hard hat and working for four hours in a Skyjack, in the mode of construction workers in the immediate vicinity of my rapidly changing hometown, to complete my knitting job. A visual of the process, below. (All photos by Caitlin Eakins)  There ought to be an international law against the dirty business of jeans manufacturing. It poisons waterways, mainly in China, prompting environmental groups to raise the alarm against the devastation to communities and local ecosystems, yet consumers around the world continue to cycle through jeans, for work and in slavish loyalty to fashion trends. Even on the small off-the-grid Gulf island of Lasqueti where I do much of my work, there is a constant oversupply of denim at the local Free Store. Too ugly or thrashed to be snapped up for the price of zero, they are destined for the landfill where the toxic dyes are left to leach into the ground.  Jeans reflect the West Coast palette. Carlyn Yandle photo Jeans reflect the West Coast palette. Carlyn Yandle photo But, honestly, if they weren't so pretty, I wouldn't be saving them from the dump. It's that very West Coast denim palette that compels me to rescue these ripped, stained or just outdated jeans, skirts, jackets and dresses and mess with them. For the past few years I've been cutting them into usable pieces and sewing up utility items — bags, oven mitts, hot-pot mats, lumbar cushions — and before long I fell into my own tiny cottage industry stitching up utility aprons. Lately I've been working them up in quilts of high-contrast hues with frayed exposed seams or muted reverse greys, all in conversation with the coastal views just beyond my sewing table. So for environmental reasons and the pretty, durable nature of old denim, I keep innovating new uses, but my explorations into non-utility pieces (the stuff we call Art) is more about the culture embedded in all those jeans: the worn knees, the rips, the stains that all speak to the physical work people do on this off-the-grid island community to sustain them. I dabbled with undulating appliquéd fields inspired by the coastal climate and vistas but lately I've been more interested in exploiting the sculptural possibilities of this weighty, stiff fabric. Enter my latest exploration: large-scale macrame.  Knotting seemed like a natural way to enhance dimension, and it's relevant to this island community where knowing a few useful knots is an essential skill and in wide evidence. It also speaks to the late-'60s/early '70s back-to-the-land counterculture that defines Lasqueti. I liked the idea of creating a large-scale fringe for this place on the fringes of urban life. (Fun fact: The 13th-century Arabic weavers' word for "fringe" is "migramah", which eventually became known as "macrame".) I gave myself some rules of engagement (like I do) to create a pattern. 1) The strands would be all three-inch strips. 2) The overall length would be largely determined by the number of strips I could squeeze out of an average size of jeans. 3) I would work from dark jeans to light to dark fabrics, to create a highlight in the centre of the piece. 4) The overall width of this super-fringe would be determined by the piece of driftwood I selected. Fifty-five hours of knotty work later I completed 28 Jeans: Denim Ombré, a wall-mounted macrame work that continues to inspire more ideas and more questions: How can I achieve a more sculptural effect? How can I find that beautiful place between pattern and collapse? And most importantly: Why did I throw away my old macrame magazines??  Where it all began: The Mud Girls retreat that sowed the seed for new/old building modes. Where it all began: The Mud Girls retreat that sowed the seed for new/old building modes. Playing with mainly found materials, and whenever possible with other people, offers me the chance to learn about properties and potential of those throw-away materials as well as about collaborative problem-solving and new/old modes of social interaction. I try not to overthink that link between materials and the inherent social nature of our species but just go with the urge to make the connections. Working with cob – natural concrete that uses clay, sand and straw – provides a glimpse of an alternative to the inevitable glass-tower existence, the reliance on fossil fuels and the hazardous extraction and distribution process. There’s nothing like bunker fuel hitting the local beaches or the growing Pacific trash vortex not so far away from those freighters to inspire alternatives. The solutions to these problems require alternative thinking, which depends on playing with ideas.  Excavating as exercise: Digging out a 60-inch diameter, 18-inch-deep hole. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Excavating as exercise: Digging out a 60-inch diameter, 18-inch-deep hole. (Carlyn Yandle photo) I got that first glimpse in a two-week cob-house-building workshop in the forest atop a Gulf Island, just days after I closed the door on my office job at a city newspaper. It was a tough adjustment, moving from a hierarchical corporate media culture to a loose, collaborative course-movement. By day I hauled boulders and danced the sand into the clay with the Mud Girls, the kind of people I had never cross paths with in a Vancouver editorial department. By night I slept alone in a tent on a mossy outcrop.  Drainage is essential for natural clay-building on the Wet Coast. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Drainage is essential for natural clay-building on the Wet Coast. (Carlyn Yandle photo) How was it? my friends asked after I returned. "Wild" was the only way I could describe this foreign experience. Ten years later, I’ve been aching to dig my hands back into that feeling of the possibility of building something out of nothing, with others, testing our physical strength and forging connections with others who have a line on a local source for our materials. The project is a cob oven, on a Gulf Island. The goal is to bake a pizza by the end of the summer. Phase 1 is complete: creating a solid foundation for the oven. This is essential for protecting the cob from the Wet Coast climate.  Teach your children well: Hands-on learning that building materials are as close as under foot. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Teach your children well: Hands-on learning that building materials are as close as under foot. (Carlyn Yandle photo) The first two days were all about excavation. I hacked through thick salal root and hauled out bucket after bucket of compressed silt aggregate. The kids were eager to get into the act of shoveling the dirt onto the screen, then pouring water through the screen until just the rocks remained. I laid down some found French drain then back-filled with the gravel and stones until the site was pretty much level. Next up: Building a dry-stack stone foundation – with a little help from my friends. Stay tuned.  Toybits (green) - made from broken toys (Carlyn Yandle photo) Toybits (green) - made from broken toys (Carlyn Yandle photo) This may be the third or fourth column/post I've written that could come under the headline, 'Overthinking will be the death of me.' There is definitely a book in there somewhere about the power of overthinking to sabotage the creative process. My latest overthinking sabotage occurred as I was experimenting with binding up broken toy bits (consciously not overthinking why). I was taking care of my sister's kids while idly binding one green toy remnant to another. At some point, the curious object appeared to be done. And it was good. It's an intriguing object but when photographed is also a visually absorbing abstract. It has richness in its ability to conflate the second and third dimensions. It is heavy with cultural reference yet lightly humorous. I was onto something.  Toybits (black) - final version (Carlyn Yandle photo) Toybits (black) - final version (Carlyn Yandle photo) After a couple of hours I quit because it clearly would have no logical endpoint. But if there's one thing I've learned about the creative process it's to let the failures hang around and stink up the joint for a while. In my experience, the only way to get to the source of the stench is to keep it in the periphery. And a couple of days later it came to me: I was so hell-bent on the outcome I had completely negated the making, which, when referring back to the green toy-bits cluster, was the essence of the thing: play. I took it all apart, then started over, finding the fit between one bit to another bit, then adding one bit where it fit. (Maybe the book should be in Dr. Seuss language). It had a beginning and an end, and the entire process was an adventure without a map. The result is a sculptural object with implied power that appears as part engine, part vehicle, part robot. It has composition, balance, architecture, intriguing sight lines and varying perspectives. It has something to tell me: Your instincts are good, keep going. From the junk of life emerges new life. You can see it in the above photo; it's a mess. Even as I was binding it I thought, This is not working, this is not working. Why is this not working? It has no balance, no composition. it is artless. And it was a chore from the get-go.  Toybits (black): first attempt (Carlyn Yandle photo) Toybits (black): first attempt (Carlyn Yandle photo) So, like every creative I know, the ol' mental processor starting whirring away in the background, rolling over this concept. Friends and I talk about this slightly obsessive stage when developing a new work. You're still functional in your daily routine but that whirring puts you in a slightly distracted state. It's sort of like falling in love; there's always something there to remind you of that growing passion. And when I fall in love with an idea, I fall hard. I'm consumed by the topic like the Paul Rudd character in The 40-Year-Old Virgin who can't stop talking about Amy or The Big Lebowski's John Goodman character who links any conversation to his days in 'Nam. I've been seeing toy-bits inspiration everywhere, including in a car column in the morning newspaper. The picture of an engine reminded me of the toy-bits clusters and suddenly I was shoving aside breakfast dishes and breakfasting people and dumping my hoard of broken toys onto the table. I will make that engine-y thing, I said. And therein lies the fatal flaw. A Christmas Day king tide served up some thick snarls of bull kelp and I seized on an idea.  Kelp Skein, in progress. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Kelp Skein, in progress. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Actually, I had no particular idea in mind; only quite a bit of wonder at the quantity of the stuff. After dragging great hunks of it back to the deck, I started to play. I organized the stuff into visual categories, and soon I was winding the tendrils into a skein, and slicing the bulbs into vessels. Some experiments were left in the elements and others brought indoors to desiccate (and hopefully not moulder and go rank). Will my 20-pound giant ball shrivel up and break apart? Will the vessels turn into leathery cups? Time will tell and failure will be a teacher. In the meantime, I turn to the research portion of this playing with materials which leads to playing with ideas.  Kelp bags helped preserve harvests of shorebirds. Kelp bags helped preserve harvests of shorebirds. No surprise this high-tensile, miraculously durable, bouncy stuff has had many practical uses since ancient times. The first nations of New Zealand called it Rimurapa, and cut into the honey-comb-like walls of the blades to create bags — Poha — to preserve and cook their harvests of muttonbird, an oily shorebird. Or they cut slits in the bags, filled them with shellfish, starfish and abalone, then tossed them in the water to seed coastal areas. Or they attached two inflated pohas and used them as water-wings in strong currents. Or lined woven reed hulls to make super-buoyant Zodiac-type vessels. The first nations in these parts transported oolichan oil. That's all before listing all the nutritional attributes, and there was plenty of play in that bull kelp too. The high concentration of alginate makes the material a natural rubber ball.  California maker Geri Swanson's kelp rattles are part of her nature-crafty product line. California maker Geri Swanson's kelp rattles are part of her nature-crafty product line. If you image-search "use for kelp" you're hit with a barrage of ideas for thick rings of pickle recipes and a lot of crafty ways with kelp. Among the fascinating findings are the Seattle area sound performance artist Suzie Kozawa, who makes wind instruments from bull kelp; and Everett, Washington fiber artist Jan Hopkins who combines bull kelp with sturgeon skin and other materials in her conceptual vessels. But the beauty of the google-search is finding what you're not looking for, the unintended learning. That happened when I came across American artist/designer/maker Scott Constable and his manifesto-in-the-making of ‘exuberant frugality’ (fine video in that link) that defines what he calls Deep Craft, based on the principles of deep ecology. Like Constable, I am intrigued by the inherent qualities of bull kelp and am still playing with how to make the most of those characteristics. He is thinking about bronze-casting the bulb and thick stem portions as furniture legs. I will stick to the meditative motions that will grow the kelp skein while keeping me thinking.

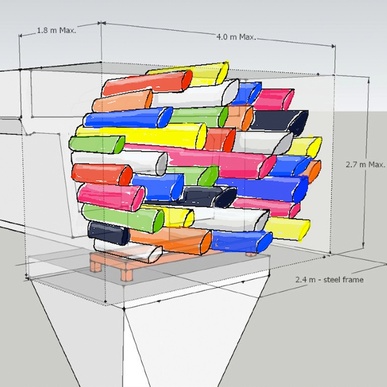

It's one thing to dream up an idea for the back end of the elevated Canada Line track and quite another to see that dream come together in a mammoth aluminum sculpture.  Metal fabrication at the Select Steel shop, Delta. Carlyn Yandle photo Metal fabrication at the Select Steel shop, Delta. Carlyn Yandle photo So when I got my first glimpse of the progress of Cluster at the metal fabricators this week, the piercing clang and whine of the shop suddenly seemed to give way to the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Whoa. It was exactly as I had imagined it, except for the immensity. That something so voluminous could come out of a bundle of bubble tea straws was sort of short-circuiting my brain. Well?, their faces seemed to ask. "It's... very... big," I said, immediately thankful their earplugs spared them from hearing the bleeding obvious.  Cluster concept sketch (image by Carlyn Yandle) Cluster concept sketch (image by Carlyn Yandle) Of course, no one sees these moments of shock, nor all the anxiety, revelation, frustration, obsession typical of the emotional swings that go into the creation of public artwork. When Cluster is hoisted into position next month, its narrative will be in the eye of the beholder, its entirety read in an instant. But a new Richmond Art Gallery exhibit (opening next Friday evening, Sept. 5) is pulling back the curtain on the process behind five public artworks that dot the city, in its City As Site show, curated by RAG director Rachel Lafo. Here is where visitors will see evidence of the beginning of the ideas that were pitched, developed, reworked, and finally translated into forms for public placement. Combined with that focus is a survey of all artwork in the local public sphere that is defining Richmond as not just another clutter of condos but a specific space in a particular time.  Metal fabricator Jordan Thys at work. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Metal fabricator Jordan Thys at work. (Carlyn Yandle photo) For me, laying bare some of my half-baked early concepts and awkward sketches that led to the development of Cluster (as well as the Crossover crosswalk design) is slightly uncomfortable but this is a warts-and-all display. Not shown is the high level of trust that must exist for any collaborative project to succeed: trust in one's own ideas, the physical properties of the materials, the skill and temperment of fabricators, the foresight of structural engineers, and the patience of the commissioning bodies. Public art projects come with the headache-y package of issues of insurance, permits, budgets, timelines and many unforseeables. In short, it's much more than a good idea. Embedded in those physical projects is the intangible quality of faith. Cluster isn't done yet, but I have faith that it will soon be a thing in the manufactured landscape that will spark conversation, which will connect people and by extension contribute toward a unique, vibrant community and cultural hub. Fingers crossed anyway. |

Sharing on the creative process in long-form writing feels like dog-paddling against the tsunami of disinformation, bots, scams, pernicious sell sites and other random crap that is the internet of today. But I miss that jolt of inspiration from artists sharing their work, ideas and related experiences in personal, non-marketing blogs, so I'm doing my part.

browse by topic:

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed