Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

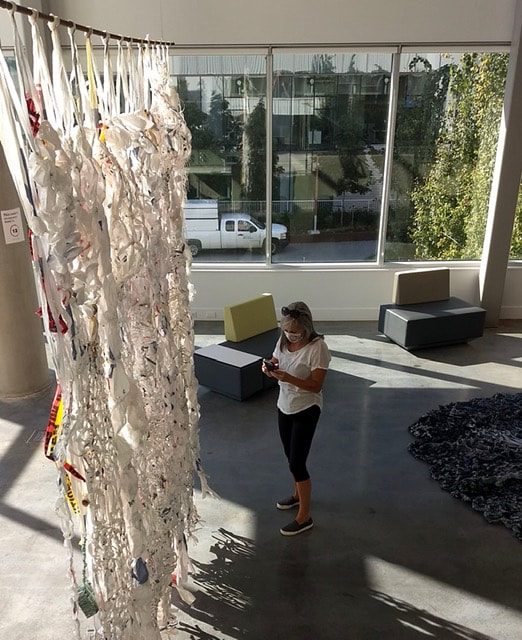

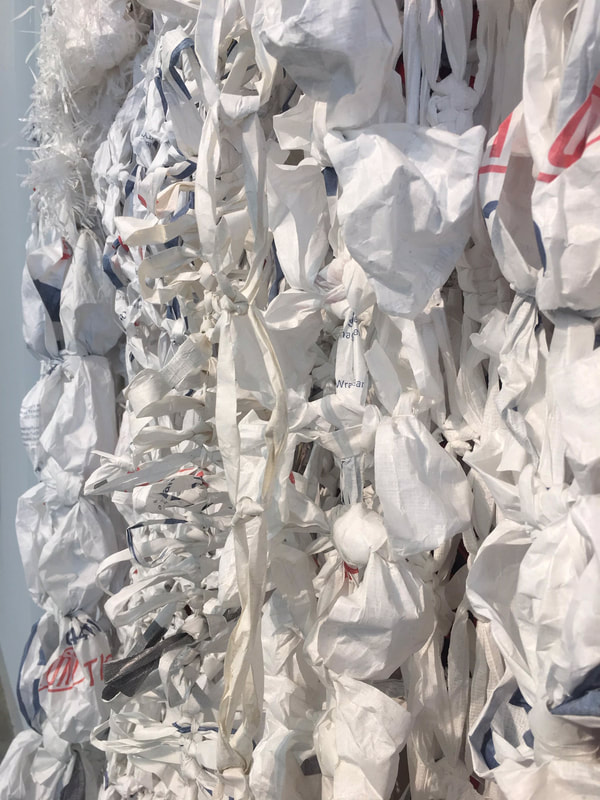

Where is the joy when you’re living in a time of a global coronavirus pandemic and a local toxic-drug epidemic? What is the use of making when your city is seized by global investment-real estate schemes, when there’s too much stuff in a overheated planet and a hateful, superpower president next door? These questions ricochet around my brain, only abating when this futile, exhausting expenditure of energy hones in on the rote activity of knotting and needleworking. The hand-wringing falls into rhythm as I grasp at lost, tossed threads that I make whole and into whole new ideas. Making is a very personal physical reaction to perilous times and unstable circumstances but working with found fibre is also an intrinsically social action that weaves in disparate economic circumstances, language, race, age and abilities. Braiding, stitching, knotting, needleworking create resilient connective tissue between one body and another. Strands thicken into solid links between the ancient and the modern, utility and self-expression, the digital and the physical, the personal and the political. By exploring the inherent qualities of abject manufactured material, the body binds with other bodies and other places, some known, some not. It is work, but outside the tumultuous dominant economic system. It is an experience of the history of production and distribution through the material at hand. Even in these times, when gathering around a table is a hazardous activity, when our pack species is feeling at loose ends, masked up and reluctantly apart, the tactility of rote hand-making grounds us into the here and now, one stitch, one loop, one knot at a time. We grasp at the tendrils, continuing the work, with the results standing as artifacts of a time, place and our individual and collective states of being. Three major works created over one year remind me of the uncertainty, the panic, the perilousness of these times, and of the solace gained through individual making and the joy of making with others. The three are relics of two years of material research that culminated in a Master of Fine Arts 2020 exhibit set up one day before the university locked down. 1. Scaffolds2. Resurge3. HearthBack when I was still transitioning from workaday newspaper editor to mainly work-for-free artist I applied for a Nexus card. "Whaddaya you do for a living?" asks the clerk in her American drawl, without looking at me. When I get this question I always wish there was an easy answer, some simple keystroke like in the relationship status options on Facebook. "It's complicated," I say. She sighs. I start in about how I was a journalist but then quit to go into full-time Fine Arts studies, then after graduation I got a studio and am now developing an art practice and doing work for upcoming projects... and stop as her eyes fall to half-mast. We go back and forth for a while like this when she announces: "I'm gonna put you down as housewife." Even though I've always been self-supporting I decide not to waste my breath defending my non-conforming life choices. But really, I'm using the best skills I have to be a contributing member of society and I'm grateful to be a part of the ever-expanding, borderless community of crafters, craftivists and visual artists, all connected beyond language by hand-making for peace of mind and social, political connection. Craft creates wellness, it brings humanity during turbulent times, it breaks down hierarchies and is the connecting thread between those who make for personal, tactile pleasure or for use and those who make art for art's sake. Craft is as at home in the home as it is on Etsy or in the white-cube gallery. It has footholds in ancient practices and the avant-garde. It complicates categorization and won't be fenced in (or out).

Making and their makers form an essential humanizing force more encompassing and enduring than even advanced capitalism but there's no way to show that value on a Nexus form.

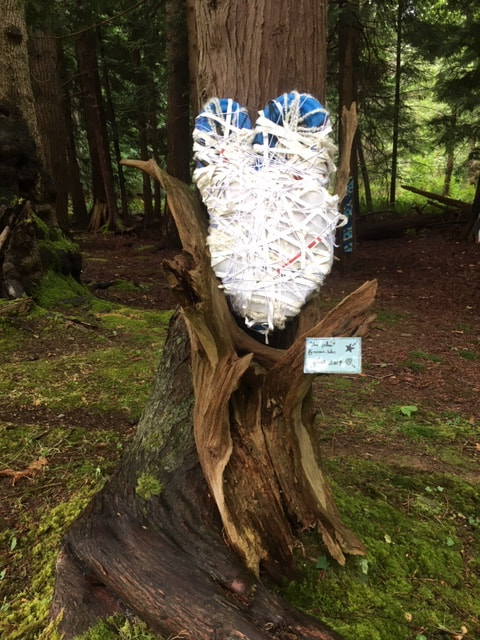

I reject that line of questioning. And I am not married to a house. Everyone is feeling that relentless creep of plastic that is threatening to consume us, the consumers. I felt myself drowning in the tsunami of stuff over this past year of grad studies at Emily Carr University. Art, as one instructor stated, is a wasteful business. Even as I retreated back to my green, pristine Gulf Island I was hit with it at the end of the long drive through forest to the local dump: a mountain of garbage. This, from a small off-grid community known for its environmental consciousness. My art practice is driven by a need to physically grapple with the unfathomable when words are not enough. In the strange way that an idea for an artwork takes hold, that sight of that mountain of petroleum-derived recycling-rejects led to my latest project: Foundlings. For a while I’d been trying to land on a low-barrier, low-skill technique that could involve kids in the making of objects from found, non-recyclable and non-biodegradable materials. Then I landed on the work of late American sculptor Judith Scott, whose many exhibitions of her curious bound and woven fiber/found objects have led to discourse on “outsider” art, disability (she was profoundly deaf, non-verbal, and had severe Down’s Syndrome), intention, new sculpture forms and the privileged art world. Within a month of escaping the art institution I was driving a pickup-truckload of colourful non-recyclable, non-biodegradable bits from the home-grown garbage mountain to the island’s only elementary school. Before we got to the making part I sat down with the students and shared some images of Scott’s work for inspiration. We talked about how this artist’s method of wrapping, binding and weaving fibre around objects adds curiosity to what is on the inside. We talked about how working with familiar objects and materials in unusual ways can lead to new ideas. And we talked about how an object can be terrible and beautiful at the same time, does not have to be a recognizable thing nor have utility. We worked over time on the pieces, some kids on their own and some in groups of two or three, adding even more fibre and found plastic detritus from their year-end trip to the local provincial marine park. On the final day of school I arrived to pick up the final pieces and was astounded at the creations. They were richly textured, humorous and foreboding, and proof of why I collaborate with children: they consistently demonstrate the importance of letting hands and imaginations fly.

They each titled their pieces in their own hand and I installed them for exhibit on forest plinths (moss-covered stumps from the last big clearcut) in time for the annual Arts Fest. With no chance they’ll degrade in the weather they remain there, pretty and pretty disturbing: our inescapable stuff. It is excruciating to junk a piece of, well, in this case, junk. But it has to be done. Such is the reality of the Vancouver maker who likes to work large but lives in a small space. So I sacrifice Charm Bracelet, following the end of its one and only showing at the premiere exhibit of the AgentC Gallery in Surrey this week.  I'm actually hoping that some other people will junk this on my behalf because I don't trust myself. I may, at the last minute, decide to keep it for future shows. Even as a tinny little voice in my head pleads, Don't toss me out; I'm part of you. Don't abandon part of you! the more practical adult is adamant: Do not burden your future with this heavy, rusty chain of old bed springs and rusty tools. The whole dilemma is fitting for this piece designed to evoke ideas of memory and weight, of hoarding and stashing (the materials were found in a Surrey residential lot, just a small fraction of household junk dumped by the former owner). It speaks to our attachment to useless things that are dragging us down. Got it: lose the stuff, embrace the space. I will not sabotage the plan. Not this time. Really.  "Hazel Cheng, 21, Bedroom in Family Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) "Hazel Cheng, 21, Bedroom in Family Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) What I’d really like to see is a ‘realitylink’: an aggregate site devoted to photo tours of real Vancouver homes where people actually live, cook, eat, sleep, play, fight, have babies, raise children, have pets, grow old. Except there’s no incentive for people to post photos of their very personal spaces for the viewing interest of perfect strangers. Occasionally, though, you get a glimpse of that rich world of personal spaces. That’s why I lingered so long at the final project of Mary Wendel Genosa during the Emily Carr University graduation show opening last weekend, and why I went back a few days later. The graduating photography student's compelling large-scale portraits of twentysomethings in their sleeping quarters, Bedroom Biographies are a glimpse into the values of the newest generation of adults. The narratives are rich here. There is the straddling of childhood and adulthood; the impermanence at this time of life; dislocation and alienation; engendered spaces and objects. Each 91cm X 60cm tableau is rich with signifiers and most devoid of self-consciousness. There is sincerity in each image, an inherent trust between subject and photographer. The accompanying hardcover book covering Wendel Genosa’s complete series includes reflective commentary by the subjects, elevating them from person-objects to thinking individuals. But it is their personal spaces that speak loudest of their struggles and their need for solace and comfort. You can see it in the stuff, in the lack of stuff, the kind of stuff, their arrangement of the stuff. If you believe what you see on realtylink.org, most Vancouverites live in clutter-free, pristine homes with gleaming hardwood and stainless steel appliances, matchy-match, neutral livingroom furniture and large abstracted landscape paintings on the otherwise empty gallery-white walls. There’s nothing like clicking on the “additional pictures” or "virtual tour" to realize that your own home (and by ‘your’ I mean ‘my’) is an unphotogenic jumble of memory-things you can’t get rid of for sentimental reasons. Your space is unsuitable for realtylink viewing because it is not a market-commodity; it’s a refuge from all that superficiality.  "Messica Mae, 26, Bedroom in Shared Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) "Messica Mae, 26, Bedroom in Shared Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) Unreal real-estate photo tours can suck us into believing that everyone else is living a peaceful, uncluttered, happy existence, especially those in their 20s. These weighty portraits remind us of those early adult years that were the best of times and the worst of times. Real life is much more messy. *** The Show 2015 continues at the Granville Island campus until May 17, 10 am to 8 pm Monday to Friday, 10 am to 6 pm Saturday and Sunday. Take in one of the free one-hour tours on Saturday, May 9, 1 pm, Thursday, May 14, 6 p.m or Saturday, May 16, 1 pm. (Meet in the foyer of the North Building five minutes prior to a tour.) |

Sharing on the creative process in long-form writing feels like dog-paddling against the tsunami of disinformation, bots, scams, pernicious sell sites and other random crap that is the internet of today. But I miss that jolt of inspiration from artists sharing their work, ideas and related experiences in personal, non-marketing blogs, so I'm doing my part.

browse by topic:

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed