Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

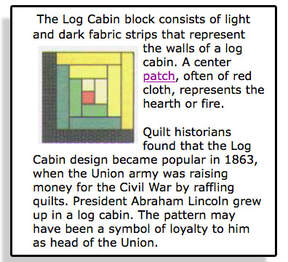

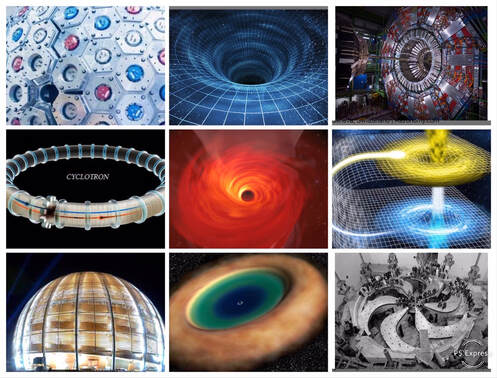

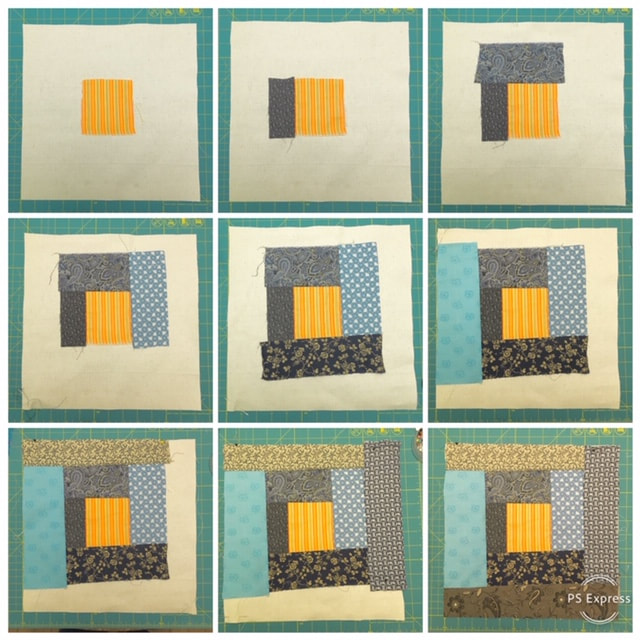

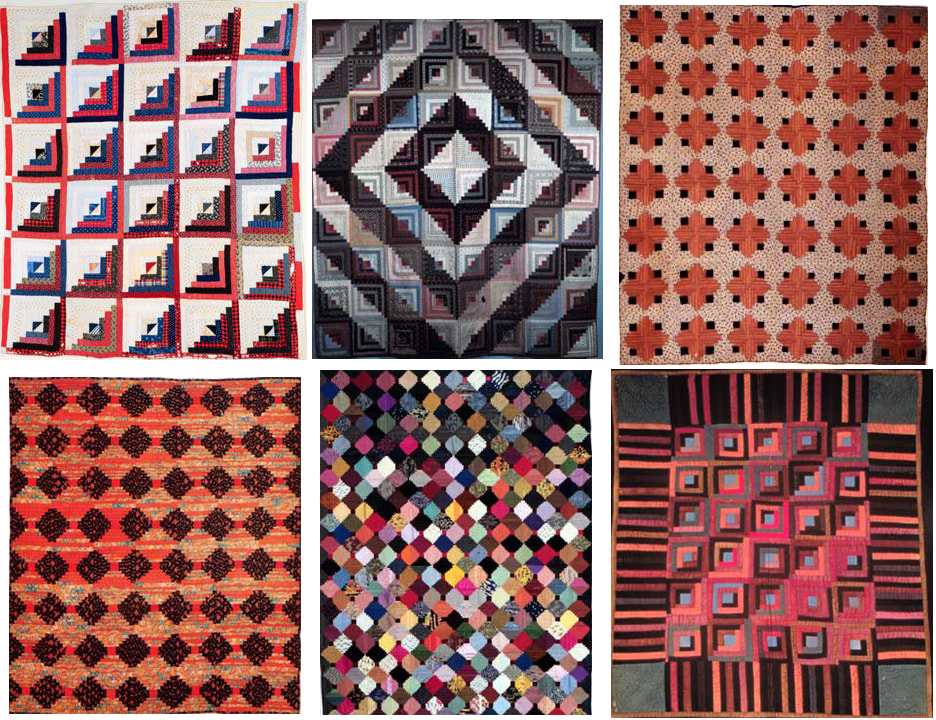

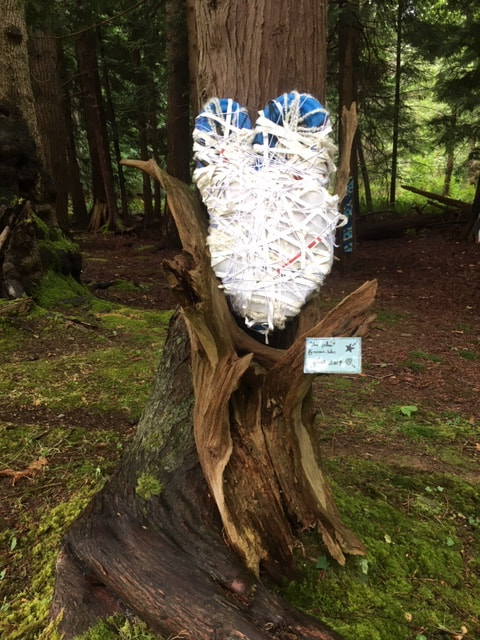

I have this idea for building healthy community in this pretty/cold city through hand-making. It’s a process of making peace with ourselves and connecting with others, transforming individualized desires (thanks, capitalism) into shared desires for a sustainable life and world.  Vancouver artist Jenn Skillen — collaborator No. 1 — beta-tests a freeform, no-measure hand-stitched log cabin block method. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Vancouver artist Jenn Skillen — collaborator No. 1 — beta-tests a freeform, no-measure hand-stitched log cabin block method. (Carlyn Yandle photo) That's the idea. 'How' is the big question. I start with a few rules of thumb. (I love that phrase for its controversial origin that is a deep-dive into human history and etymology, but also for the visual of the hand-as-tool.) First, the activity must be low-barrier enough to open it up to as much collaboration as possible — no need for special skills or equipment or fees or even shared verbal language. Second, the project must use only found material: freely available, with no better use (because there's already too much stuff in the world). Third, the project must spark interest, otherwise, why would people bother? A decade ago, these rules of thumb resulted in The Network, an ever-growing public fibre-art piece engaging a wide variety of folks around Vancouver, co-created by Debbie Westergaard Tuepah. That knotty piece continues to weave through my work, mummifying a perfectly good painting practice, winding around ideas of alternative space-making, shelter, and safety nets. Now it's needling into my current project: the Safe Supply collaborative quilt. 'Safe supply' were the two words on the lips of the crowd at a CBC Town Hall gathering two months ago. Providing a safe supply of opioids would go a long way to addressing all the problems and fears raised by everyone from student activists to local businesses, from concerned politicians and developers to Indigenous elders: the toxic-drug death epidemic, violence, homelessness, sexual exploitation, theft, vandalism, mental illness. A safe supply is inherent in the view of addiction as a public health issue, not an individual, moral failing.  'Kettling' homeless people into Oppenheimer Park has resulted in a colourful display of a national humanitarian crisis. (Carlyn Yandle photo) 'Kettling' homeless people into Oppenheimer Park has resulted in a colourful display of a national humanitarian crisis. (Carlyn Yandle photo) Ground zero of this humanitarian crisis is the colourful, chaotic tent city crowded in Oppenheimer Park straddling Chinatown and the old Japantown. The sight of all those bright, tenuous shelters layer up with this history of racism and injustice, stolen land and lives, and soon I am binding up ideas of found colourful material and that call for Safe supply!, embedding it all in a design, with designs for this as a group project destined for exhibit in more privileged spaces. It is planned as a comforting activity in this often ruthless, discomforting city: a dis-comforter.  Historical clipping from the llinois State Museum website reveals the log cabin quilt has ties to ending slavery. Historical clipping from the llinois State Museum website reveals the log cabin quilt has ties to ending slavery. I begin this overarching theme one block at a time, and that block is, fittingly, the traditional 'log cabin.' There's a long history of the log cabin block, ingenious for its simple construction that makes use of even the smallest, thinnest available scraps as well as its history as a vehicle for social justice. I am attracted to the name that stands as aspiration for home and all that that entails, beginning with the hearth, the centre of the block. From the hearth, the block is built in a spiral of connected scraps to form a foundation for countless quilt designs (traditional examples below). The work has not yet begun but like all collaborations it begins with faith in people and trust in my practice. Something will emerge. We will engage. We will generate some heat in this log-cabin community. Some useful how-tos and overall pattern examples: About a decade ago I stumbled across Latvian-American mathematician Daina Taimina’s curious crochet abstractions. What's not to love about needlecraft (and needlecrafters) that advances modeling of non-Euclidean geometry?  Hyperbolic crochet, by mathematician Daina Taimina. Pic from rixc.org Hyperbolic crochet, by mathematician Daina Taimina. Pic from rixc.org I’ve been needling away ever since at the power of domestic materials and methods in making new forms (and new ideas). Most recently I’ve been fascinated by the sculptural potential of smocking that was once a feature of every little-girl dress before the fantastic elastic plastic age hit. Smocking expands and contracts rigid material and turns area into volume. Best of all, it’s a slow-craft, inwardly-focused, rote activity that is an essential thinking tool for me: when the hands are busy (with something other than the damn iPhone) then the mind is free to wander. And where I've been wandering around these days is space, from the macrocosm to the microcosm. For the last year I’ve been meeting regularly with a physicist and an engineer from the particle-accelerator lab at UBC and two scholars in the field of arts, for a project through Emily Carr University that explores the possibilities of 'co-thinking' or 'hybridized thinking’ between artists and scientists.  Circular patterns of the schematics of astrophysics and nuclear medicine are seen in the UBC particle-accelerator building itself. Circular patterns of the schematics of astrophysics and nuclear medicine are seen in the UBC particle-accelerator building itself. After I got over the initial shock of being invited to join the dozen research assistants on this project (having barely squeaked through Math 11 and remaining the problem child at my tax accountant's office) I realized that I would not in fact be taxed with fully grasping unfathomable ideas of space-time or the confounding mechanicals inside UBC's cavernous particle-accelerator building. Instead, my role as a facilitating artist includes producing an artwork out of this whole experiment, for a group exhibit later this winter. So why not smocking?  Material research includes reviewing the history and applications of an ages-old textile technique. Material research includes reviewing the history and applications of an ages-old textile technique. There's something zingy about using the most basic of methods — tying string knots in fabric — as I grapple with concepts like infinity, black holes, space-time, and a contracting universe. As I play with folding 540 square feet of area into volume, making a shape with no beginning nor end, I wonder about the possibility of doing the opposite of Dr. Taimina: making a model that is looking for the math. The shape that is taking shape is as convoluted as many of our group discussions, and sits in that unsettling space between pattern and chaos, structure and collapse. It's as precarious as Leaning Out of Windows, the name of this four-year co-thinking project, yet tempting enough for the possibility of catching some new views. Everyone is feeling that relentless creep of plastic that is threatening to consume us, the consumers. I felt myself drowning in the tsunami of stuff over this past year of grad studies at Emily Carr University. Art, as one instructor stated, is a wasteful business. Even as I retreated back to my green, pristine Gulf Island I was hit with it at the end of the long drive through forest to the local dump: a mountain of garbage. This, from a small off-grid community known for its environmental consciousness. My art practice is driven by a need to physically grapple with the unfathomable when words are not enough. In the strange way that an idea for an artwork takes hold, that sight of that mountain of petroleum-derived recycling-rejects led to my latest project: Foundlings. For a while I’d been trying to land on a low-barrier, low-skill technique that could involve kids in the making of objects from found, non-recyclable and non-biodegradable materials. Then I landed on the work of late American sculptor Judith Scott, whose many exhibitions of her curious bound and woven fiber/found objects have led to discourse on “outsider” art, disability (she was profoundly deaf, non-verbal, and had severe Down’s Syndrome), intention, new sculpture forms and the privileged art world. Within a month of escaping the art institution I was driving a pickup-truckload of colourful non-recyclable, non-biodegradable bits from the home-grown garbage mountain to the island’s only elementary school. Before we got to the making part I sat down with the students and shared some images of Scott’s work for inspiration. We talked about how this artist’s method of wrapping, binding and weaving fibre around objects adds curiosity to what is on the inside. We talked about how working with familiar objects and materials in unusual ways can lead to new ideas. And we talked about how an object can be terrible and beautiful at the same time, does not have to be a recognizable thing nor have utility. We worked over time on the pieces, some kids on their own and some in groups of two or three, adding even more fibre and found plastic detritus from their year-end trip to the local provincial marine park. On the final day of school I arrived to pick up the final pieces and was astounded at the creations. They were richly textured, humorous and foreboding, and proof of why I collaborate with children: they consistently demonstrate the importance of letting hands and imaginations fly.

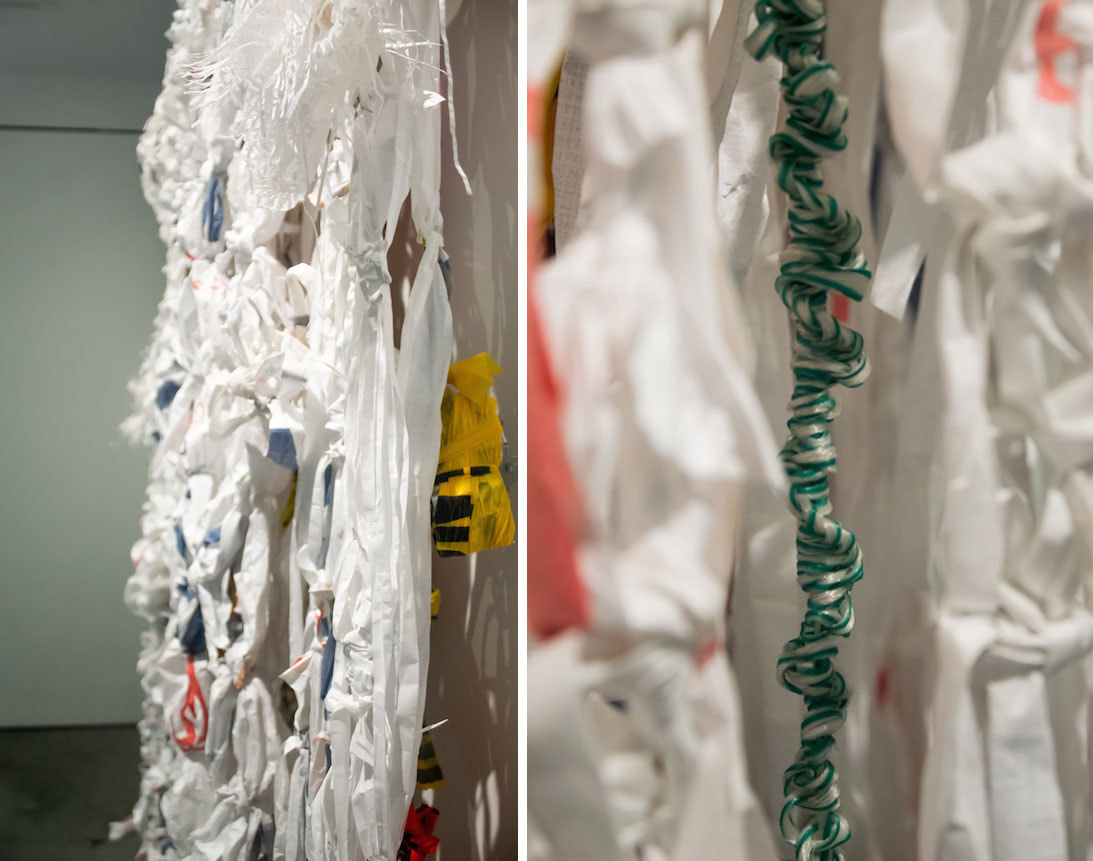

They each titled their pieces in their own hand and I installed them for exhibit on forest plinths (moss-covered stumps from the last big clearcut) in time for the annual Arts Fest. With no chance they’ll degrade in the weather they remain there, pretty and pretty disturbing: our inescapable stuff. The brilliant part about being an aging female is your growing self-acceptance. Maybe this is because you don't feel that ever-present gaze anymore so you’re not feeling as judged. Or maybe it’s because you’ve just had enough of all that and it’s tiresome and dammit you like to be cozy so screw them. Part of my self-acceptance is stepping out of the ‘should-storm’ of art-making and doing what I love to do with my hands: hunting down materials that have already had their first use and playing up their inherent qualities through knotting, weaving, tying, stitching and binding. I want to work repetitively, easily, without technological assistance and without haste or waste. And in doing so I’m carving out space and time to calm down, reflect and to think deeper — more crucial as the distractions threaten to take over.  Nate Yandle photo Nate Yandle photo In this way the work is not just in the form or connotations but the well-being and challenge that is relatable to makers who may or may not self-identify as artists. Wrapped up in there are issues of endurance, innovation, history of labour, the learning of the skill, dedication (and frustration), the specific culture and history of the method, the muscle memory that extends back to childhood, and the relationships built through the gathering of the materials. Through this making I make some hay over the established boundaries between the privileged art world and real life, between craft and sculpture, between tactile and political action. Scaffolds is composed of found spun-polyester building wrap, tarp and nylon cord over an armature of waste construction materials including caution tape, PVC piping, rebar, conduit, baling wire, and junction boxes, all attached through simple knots. Special thanks goes to the construction workers who delivered these materials from their many jobsites to my studio for my useless work with many functions.  The other day I did this because it really needed to happen. All that gleaming new-campus architecture, surrounded by other gleaming buildings and gleaming buildings yet-to-come was begging for a little fuzzying up. I did my undergrad at the old Emily Carr University of Art and Design campus which was decidedly less smooth and metallic and more crafty, situated as it was in the Granville Island artisan mecca on the ocean's edge. I liked running my hand along the old wooden posts carved with decades of scrawled text, and all the wiring and ductwork that in the last few years looked like a set out of Brazil. I miss the giant murals on the cement factory silos next door and the funky houseboats and the food stalls in the public market and Opus Art Supplies 30 feet away from the front entrance. The new serene, clean Emily Carr building is surrounded by new and planned condos that most students could never afford, high-tech companies and, soon, an elevated rapid transit rail line. As much as I wanted to return for graduate studies, I was not convinced that I would be a good fit here, so asking for permission and access to the sign was a bit of a trial balloon for me. I got quick and full support for the idea and its installation, and now see this new white space as a blank canvas, ready for the next era of student artistic expression. This is my first solo yarn-bombing foray. A bunch of us attacked the old school back in the day for a textile-themed student show but I have yet to meet my people here. So the Emily Carr Cozy is not just a balloon, it's a flare. Is there anybody out there? As I busied my freezing fingers with the stringy stuff (in hard hat, on the Skyjack operated by design tech services maestro Brian) I kept an ear out for reaction. And it was good. Sharing the fuzzy intervention on social media (#craftivism, #subversivestitch etc.) reminds me that I am not alone in my need for needling authority. Indeed, this public performance includes behind-the-scenes connecting with my community of makers to collect their leftover yarn and thrift-store finds even before the main act. (You know who you are.) Textile interventions in the public sphere have a way of provoking polarizing responses. Some love the often-chaotic hand-wrapping of colourful fiber; others view the crafty messing with architecture with disdain of all things cozy and crafty and engendered female. I liked the idea of having to wear a hard hat and working for four hours in a Skyjack, in the mode of construction workers in the immediate vicinity of my rapidly changing hometown, to complete my knitting job. A visual of the process, below. (All photos by Caitlin Eakins)  "Hazel Cheng, 21, Bedroom in Family Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) "Hazel Cheng, 21, Bedroom in Family Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) What I’d really like to see is a ‘realitylink’: an aggregate site devoted to photo tours of real Vancouver homes where people actually live, cook, eat, sleep, play, fight, have babies, raise children, have pets, grow old. Except there’s no incentive for people to post photos of their very personal spaces for the viewing interest of perfect strangers. Occasionally, though, you get a glimpse of that rich world of personal spaces. That’s why I lingered so long at the final project of Mary Wendel Genosa during the Emily Carr University graduation show opening last weekend, and why I went back a few days later. The graduating photography student's compelling large-scale portraits of twentysomethings in their sleeping quarters, Bedroom Biographies are a glimpse into the values of the newest generation of adults. The narratives are rich here. There is the straddling of childhood and adulthood; the impermanence at this time of life; dislocation and alienation; engendered spaces and objects. Each 91cm X 60cm tableau is rich with signifiers and most devoid of self-consciousness. There is sincerity in each image, an inherent trust between subject and photographer. The accompanying hardcover book covering Wendel Genosa’s complete series includes reflective commentary by the subjects, elevating them from person-objects to thinking individuals. But it is their personal spaces that speak loudest of their struggles and their need for solace and comfort. You can see it in the stuff, in the lack of stuff, the kind of stuff, their arrangement of the stuff. If you believe what you see on realtylink.org, most Vancouverites live in clutter-free, pristine homes with gleaming hardwood and stainless steel appliances, matchy-match, neutral livingroom furniture and large abstracted landscape paintings on the otherwise empty gallery-white walls. There’s nothing like clicking on the “additional pictures” or "virtual tour" to realize that your own home (and by ‘your’ I mean ‘my’) is an unphotogenic jumble of memory-things you can’t get rid of for sentimental reasons. Your space is unsuitable for realtylink viewing because it is not a market-commodity; it’s a refuge from all that superficiality.  "Messica Mae, 26, Bedroom in Shared Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) "Messica Mae, 26, Bedroom in Shared Home" (Photo by Mary Wendel Genosa) Unreal real-estate photo tours can suck us into believing that everyone else is living a peaceful, uncluttered, happy existence, especially those in their 20s. These weighty portraits remind us of those early adult years that were the best of times and the worst of times. Real life is much more messy. *** The Show 2015 continues at the Granville Island campus until May 17, 10 am to 8 pm Monday to Friday, 10 am to 6 pm Saturday and Sunday. Take in one of the free one-hour tours on Saturday, May 9, 1 pm, Thursday, May 14, 6 p.m or Saturday, May 16, 1 pm. (Meet in the foyer of the North Building five minutes prior to a tour.) The mammoth art museum experience is like an all-inclusive resort for the mind: there's so much coming at you the brain binges 'til it can't party anymore. Unless you're an art history major, what's hanging on those soaring walls and placed on those marble floors at the big art palaces like the Louvre, the Rijksmuseum and The Met is filled with cranial-clanging mystery, intrigue, obscurity, beauty and repulsion that can crash the whole neural system in something approaching Stendhal Syndrome. There's only so much visual field one garden-variety brain can take in. You need to pace yourself, preferably over several days.  Alison Woodward's emblematic, multi-layered drawings suggest carcasses. Alison Woodward's emblematic, multi-layered drawings suggest carcasses. Same goes for big education-institution shows so this is the how I tackle the annual Emily Carr University Grad Show, now open daily until May 18 on Vancouver's Granville Island. With hundreds of final works in media arts, sculpture, industrial design, ceramics, illustration and visual arts packed into two buildings I take the cavernous rooms of randomness in small bursts over a few days, usually with one friend at a time — a sort of playdate. But the only thing organized about this date is the area of creative work we're going to linger in. It's the difference between sports on a school field and free play in the forest. The real play is in the conversation that is sparked just by being in the milieu of this cacophonous visual field. It might start off as first impressions of an individual piece but often ends up in a whole different kind of thinking, and that's where the exhilaration lies. It's all just as important in the creative process as working in the studio. The beauty of online column-writing is infinite space, so, in the spirit of the gargantuan art museum and its daunting theme-free collections, as well as the need to let the brain out to play, I present here a few of my own pics of emerging visual artists at this year's Emily Carr grad show whose works contest the two-dimensional tradition. My daily work corner is one-third of a shared 800-square-foot studio of a mouldering building in the shadow of numerous condo-tower cranes in Mount Pleasant, with a combined rent of more than $1,000 per month. In the four years that I've managed to hold onto this little space I've watched Development Permit Application signs go up on one decrepit building after another. The signs go up, then all the resident independent visual artists, industrial designers, musicians, film industry workers, writers and performers get packing. But where to go is a serious problem. A healthy city has a rich culture but the places to actually do that hard work are rare or too costly to consider in this town. Everyone knows someone who has given up trying and moved to Toronto. It's getting to the point where some artist friends have decided to remain in Vancouver — at least for the moment — because they just can't abandon the struggling cultural community. It's an odd feeling, working in adverse conditions to ensure a vibrant cultural life in the milieu of the city's glassy wealth. Surely some of those speculative development dollars could actually help stem the tide that threatens to replace every last independent bookstore, gallery cafe and theatre into one long avenue of Shoppers Drug Marts, bank branches and Starbucks. This is why, despite a general wariness about any artisan-party-backed events, I and a couple of friends hit the Fox theatre last Thursday for a Vision Vancouver-backed community forum on protecting the city's cultural spaces. When you want to be part of the conversation on this critical topic you go where there are ears. Everyone from young street performers to retired folks bent on protecting threatened venues packed the revamped former porno theatre last Thursday evening — the perfect venue for showcasing what is possible with a council that is increasingly promoting the value of city culture of all kinds. The entrepreneur behind the Fox, Ernesto Gomez (Waldorf, Nuba, etc.) was there on stage as part of a panel led by city councillor Heather Deal that included fellow councillor Geoff Meggs; Kate Armstrong, director of Emily Carr University's Director of the Social + Interactive Media Centre; and Esther Rausenberg, head of the Eastside Culture Crawl. The vibe was one of simmering frustration but there was also warmth generated by the obvious show that we are all in this together. Deal dealt her summation the next day, based on notes she was taking during the roving-mike portion of the evening: "Development needs to deliver more for local culture. Arts and culture needs to be treated as a public good. That we need zoning to enable independent businesses and cultural groups to succeed, not push them out. And that it's not just about creating studio space, it's the need for rehearsal and production space too." But things are getting better, as many noted at the forum. The relatively new food truck program and more reasonable liquor licensing laws are both driving audiences and sales at local festivals and venues; car-free events like the city's biggest free music and art fest, Khatsalano and Car Free Day on the Drive have turned radical notions into much-loved draws.  Miniature portraits by artists of the Phantoms in the Front Yard Collective Miniature portraits by artists of the Phantoms in the Front Yard Collective And the squeeze on work and show space has resulted in some fresh, unconventional art shows in opportunistic spaces, like shipping containers or urban alleys. Last Friday it was a pop-up show, Everyone I've Never Known, in three units of the retro Burrard hotel. Only in one of the most expensive cities in the world will you find serious collectors crowding into tiny hotel rooms to snap up the miniature graphite and pencil portraits — proof that artists will continue to create, even if at a scale that doesn't demand studio space.  Photo of ECUAD's South Building by Stephen Hui/Georgia Straight Photo of ECUAD's South Building by Stephen Hui/Georgia Straight When finally — yet suddenly — I graduated from Emily Carr University of Art and Design, I was done, done, done, exhausted after four intense years of input. Now I needed space for four more years of output, to practice and to develop a practice. But finding a suitable work space in this pricey city is no easy task. Self-(un)employed artists are no match for the slick technology firms and ad agencies that will pay top dollar to set up their cool premises in the port-town-era brick buildings. So we make do, sharing whatever space we can get while keeping an ear open for rumours of where we might be able to jump when the Permit Application billboard springs up in front of our crumbling building.  Intriguing shows at the Charles H. Scott Gallery include the current Hyperflat. Intriguing shows at the Charles H. Scott Gallery include the current Hyperflat. Another art school in another city might play a part in providing studio rental opportunities for its new grads, encouraging a healthy cross-pollination of creative post-school work in industrial design, animation, sculpture, painting, media arts and curatorial services. But Emily Carr University is bursting at the seams and is focused on its campaign to move east to Great Northern Way. It's a grand vision, but what will become of the Granville Island community when the two-building campus vacates? What of the dependable Opus Art Supplies, which depends heavily on the student customer base next door, as well as the other material suppliers on the Island? And the George H. Scott Gallery? Vancouver Sun reporter Daphne Bramham took on the topic this week. In her story, one of the original designers of Granville Island, architect Norm Hotson, said replacing the school with another educational institution would help modernize the zone. Or it could be re-energized as "an incubator space” for "innovators", he said, or developed into a cultural hub that might include galleries, artist studios, residencies. And he pointed to Paris’s Cité Internationale des Arts as an example.  Toronto's Distillery District was revamped into a cultural hub. (Photo from Artscape website) Toronto's Distillery District was revamped into a cultural hub. (Photo from Artscape website) It's this kind of forward thinking that could stop the downtown core and Westside from slipping into a blandly privileged area with all the cultural texture of glassy high-end condos. Granville Island needs a vibrant injection of new ideas and opportunities and Vancouver desperately needs a cultural hub, a multifunctional space with rental studios and residencies for everyone from painters to industrial designers, techies to musicians, performers to writers. Yes, it's a balancing act. Nobody wants the Island to shut as tight as a tomb at night but the neighbours won't take kindly to the place being mobbed by booze-fueled night-crawlers. Artists and students work all hours, often after a day of slinging Italian coffees or serving Public Market customers. As students we purchase our supplies on the island, we depend on the visitors for our shows and showings. Our work ensures Granville Island is a tourist draw, not a tourist trap, that it is committed to Artisan over Ye Olde, authenticity over Disney. It may sound like a pipe dream, but Granville Island was part of the inspiration that led the not-for-profit Artscape in Toronto to turn a collection of industrial buildings into a major cultural hub and tourist draw, in a remarkably short time. (See YouTube interview with Tim Jones, president and CEO of CityScape below.) |

Sharing on the creative process in long-form writing feels like dog-paddling against the tsunami of disinformation, bots, scams, pernicious sell sites and other random crap that is the internet of today. But I miss that jolt of inspiration from artists sharing their work, ideas and related experiences in personal, non-marketing blogs, so I'm doing my part.

browse by topic:

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed