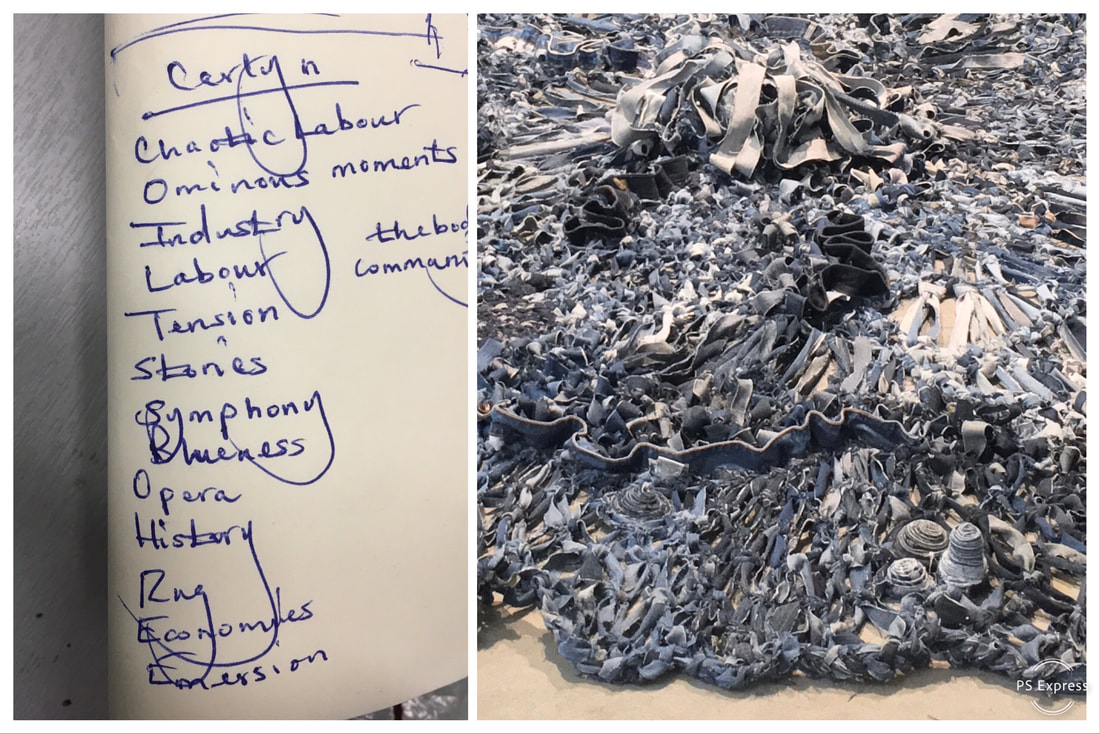

These questions ricochet around my brain, only abating when this futile, exhausting expenditure of energy hones in on the rote activity of knotting and needleworking. The hand-wringing falls into rhythm as I grasp at lost, tossed threads that I make whole and into whole new ideas.

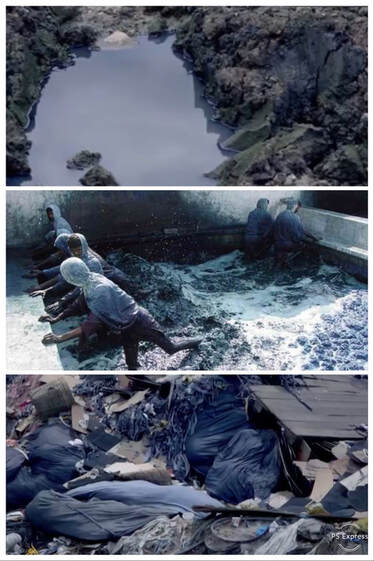

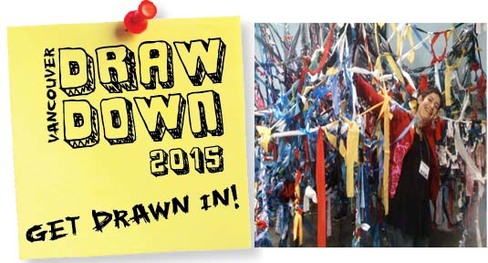

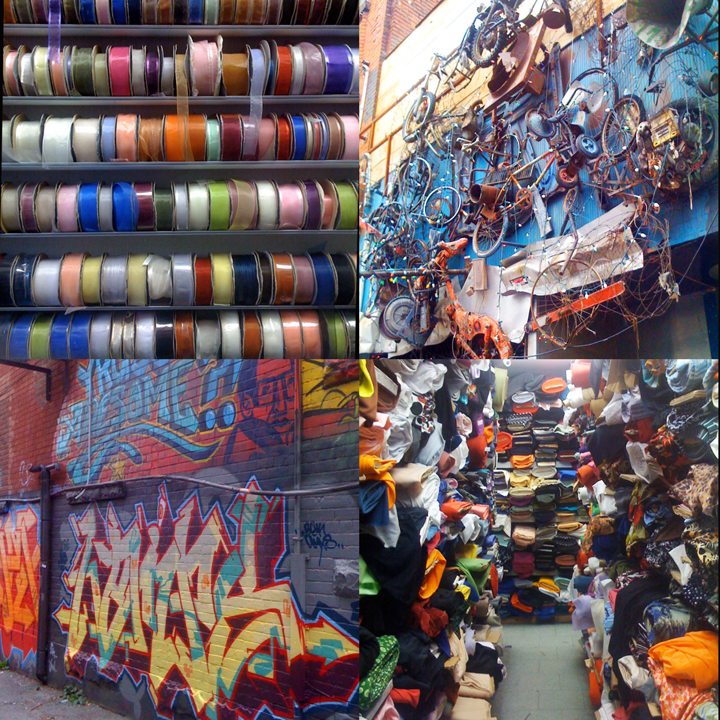

Making is a very personal physical reaction to perilous times and unstable circumstances but working with found fibre is also an intrinsically social action that weaves in disparate economic circumstances, language, race, age and abilities. Braiding, stitching, knotting, needleworking create resilient connective tissue between one body and another. Strands thicken into solid links between the ancient and the modern, utility and self-expression, the digital and the physical, the personal and the political.

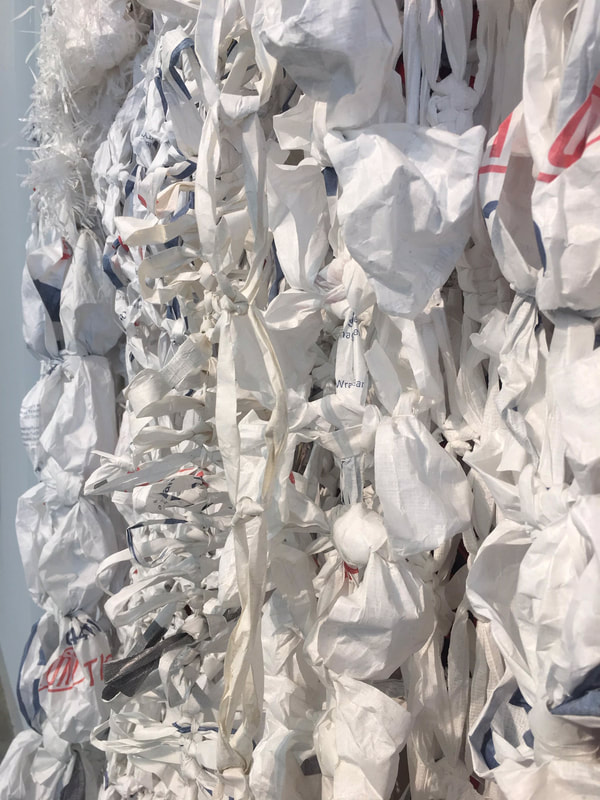

By exploring the inherent qualities of abject manufactured material, the body binds with other bodies and other places, some known, some not. It is work, but outside the tumultuous dominant economic system. It is an experience of the history of production and distribution through the material at hand.

Even in these times, when gathering around a table is a hazardous activity, when our pack species is feeling at loose ends, masked up and reluctantly apart, the tactility of rote hand-making grounds us into the here and now, one stitch, one loop, one knot at a time. We grasp at the tendrils, continuing the work, with the results standing as artifacts of a time, place and our individual and collective states of being.

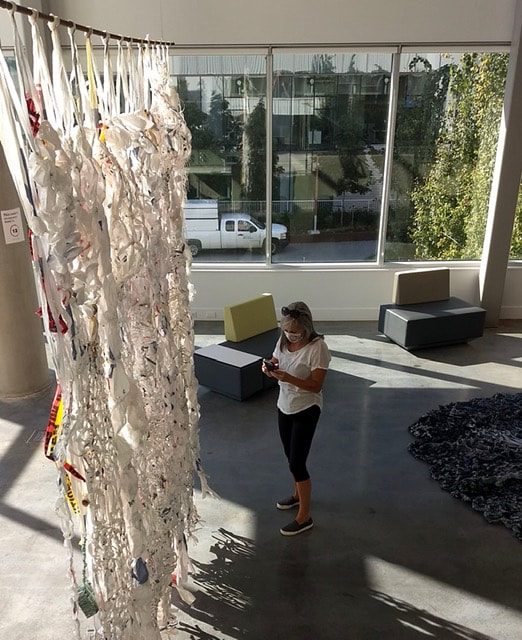

Three major works created over one year remind me of the uncertainty, the panic, the perilousness of these times, and of the solace gained through individual making and the joy of making with others. The three are relics of two years of material research that culminated in a Master of Fine Arts 2020 exhibit set up one day before the university locked down.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed