It jumped into my head while on a brilliant morning bike ride this week, after passing someone walking while talking into her phone raised in that most flattering angle of a few inches above her face. A few minutes later I passed another camera-ready performer, also sharing sunny enthusiasm into her screen. And before I finished my ride I saw another person in the same mode of performance. Aside from the tricky logistics of walking with a screen in front of one’s face, I wondered if an authentic, personal experience of the physical world is possible if you’re doing it while engaging through the mediated space of a tiny screen.

I thought I found the connector. It’s just a reflektor.

Inside Teamlab's 100,000-square-metre Borderless Digital Art Gallery. Photo by Charley Yandle

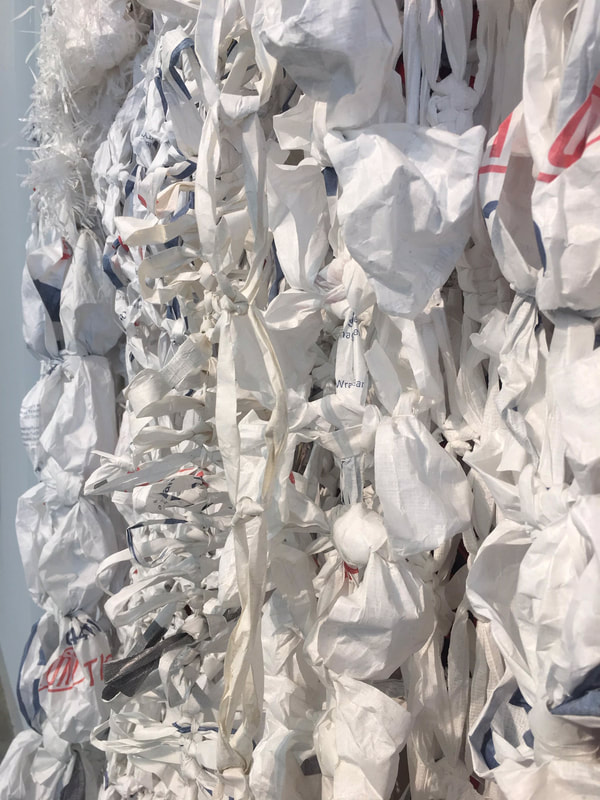

Inside Teamlab's 100,000-square-metre Borderless Digital Art Gallery. Photo by Charley Yandle Just a reflection, of a reflection, of a reflection, of a reflection, of a reflection

The several Teamlab immersive experiences in different regions were the highlight of his month-long trip. Is it just for young people?, I texted. All ages, he replied. As these massive permanent installations sprout up in shiny boom cities from Singapore to Abu Dhabi I am seeing a more dystopian view of humanity crowding into these cool sensory retreats from some burning global realities.

I scanned the website for any writing on social or political context beyond “Life is a miraculous phenomenon that emerges from a flow in a continuous world.”

Thought you would bring me to the resurrector. Turns out it was just a reflektor

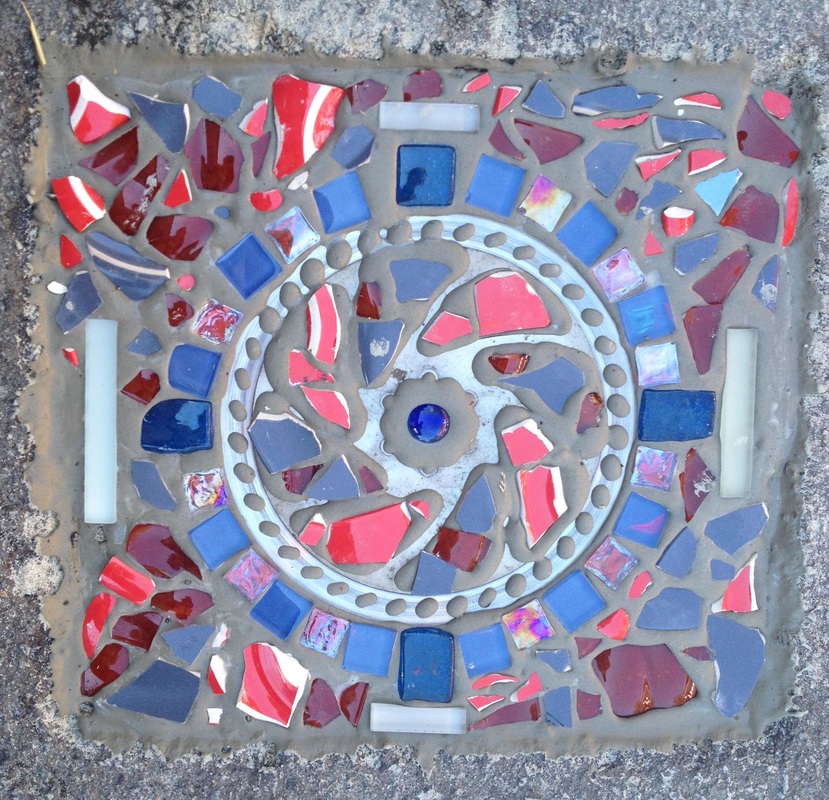

I have this idea, I said to a different young nephew a couple of months ago. Soon we were doing photo portraiture in the forest, exploring a mirror’s ability to erase the subject.

Will I see you on the other side? We all got things to hide

Crawling out of that trap, or taking a different path, may be as simple as reflecting on the sign on the door of my old apartment neighbour, a social worker: “Don’t just say something, stand there.”

Audio version of this post is at carlynyandle.substack.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed