I watched this gaunt, world-weary figure emerge in watery brushstrokes from the hand of the newspaper photographer's girlfriend. This is how she worked, in their basement suite, pulling yardage from a large roll of cheap paper, painting straight from her head and heart, with no plan to keep or show or sell her paintings. She saw that this one resonated with me too — what twenty-something in a committed relationship doesn’t have this weighing on her mind? So she gave it to me.

Hanging it felt like supporting an ally, even if it was only hanging in my dark, featureless space that nobody would see besides the boyfriend on weekends. Then one day some of his family made the trip for a visit. They complimented my hanging flower baskets, my thrifty decor. I didn’t hear until much later that the painting had become a topic of conversation among various relatives, a bit of a joke about that subject and, by extension in my mind, this girlfriend.

I had none of the inner fortitude to see this painting or my choices as acceptable and eventually I rolled it up and hid it in a closet. I married into that family within three years. The boxed wedding dress joined the poster tube containing the offending painting for two more moves until I finally ditched the artwork at the Sally Ann. The dress is another story.

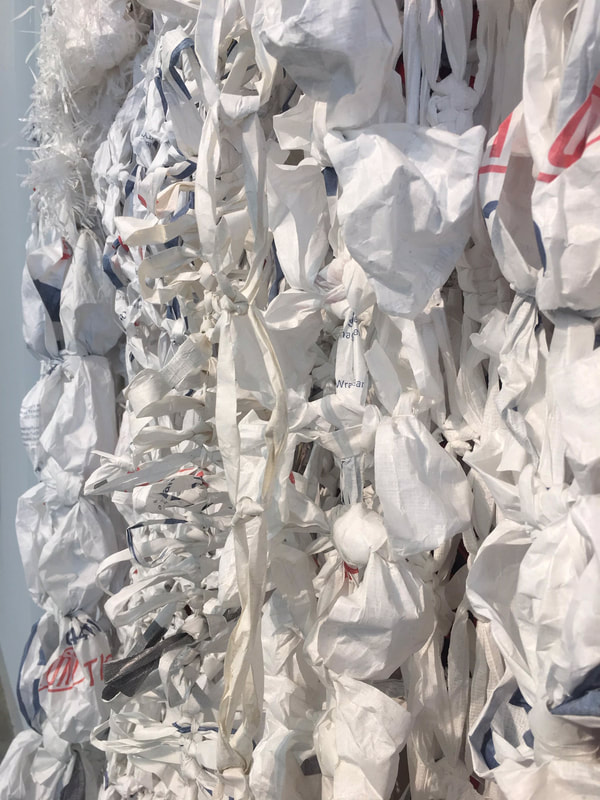

'I Dissent,' aesthetic design with a political position marking the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Acrylic on panel, 2020 (Carlyn Yandle)

'I Dissent,' aesthetic design with a political position marking the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Acrylic on panel, 2020 (Carlyn Yandle) The first is the power of attraction. Not to be confused with the pseudoscientific Law of Attraction, this is a drive to create aesthetically-pleasing, familiar domestic objects and fields that upon closer inspection have something else to say besides cozy or pretty. An early example of one of my pretty/pretty disturbing objects is Clutch (2007). Hundreds of sewing pins were pierced into a thrifted clutch purse in a colourful beaded pattern covering the entire surface. The clasp opens to reveal an impenetrable thicket of steely pointy ends.

Another valuable lesson is context, or time and place. Gallery-goers may prepare themselves to be confronted by artwork but I don’t wish that on houseguests. There are none of those Live-Love-Laugh type directives or IKEA Eiffel Towers and tulips on the walls at home, but what is there is selected to engage, not repel. Home is a place to feel safe. The studio is a place to not play it safe, but it’s still a covert operation, playing on that first impression of domestic objects that reveal cracks in the beauty of the everyday.

I’ve also learned that my creative energy comes from joy, not pain. I have no urge to make when I barely have enough hope for the day to put on pants. Heavy realities may be the driving force but the work develops from a position of hope for comfort and social connection, a hunger for nourishment of new ideas and new materials to explore. The joy is in learning while doing, imagining new collective futures.

This is how I recently became the owner of Fuckwit. I was attracted by the sweet rosebud fabric appliqued in tiny blanket stitches precise as Letraset on a lacy linen. I like the artist's choice of font and word. It’s an overt, uncomplicated work that hangs near the front door, visible before guests would even have their coat off. If people get offended, blame the artist, not me. I just like the beauty in that crack.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed