Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

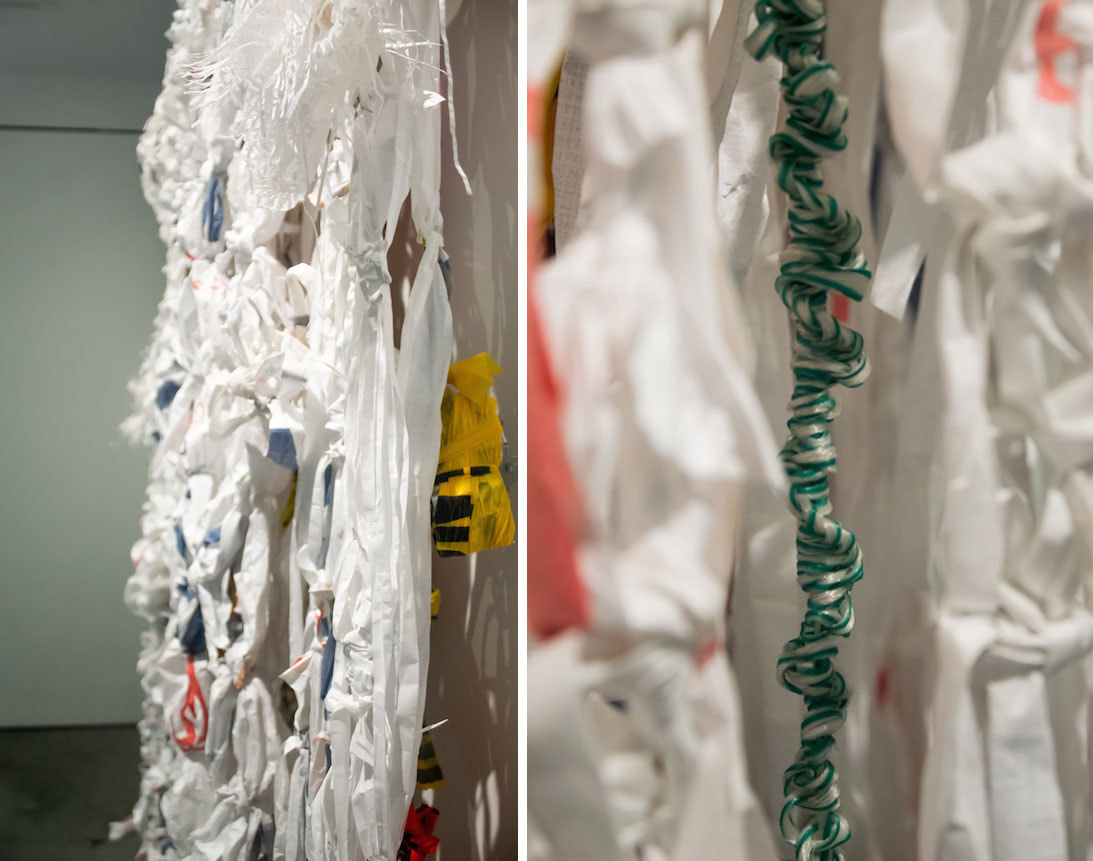

About a decade ago I stumbled across Latvian-American mathematician Daina Taimina’s curious crochet abstractions. What's not to love about needlecraft (and needlecrafters) that advances modeling of non-Euclidean geometry?  Hyperbolic crochet, by mathematician Daina Taimina. Pic from rixc.org Hyperbolic crochet, by mathematician Daina Taimina. Pic from rixc.org I’ve been needling away ever since at the power of domestic materials and methods in making new forms (and new ideas). Most recently I’ve been fascinated by the sculptural potential of smocking that was once a feature of every little-girl dress before the fantastic elastic plastic age hit. Smocking expands and contracts rigid material and turns area into volume. Best of all, it’s a slow-craft, inwardly-focused, rote activity that is an essential thinking tool for me: when the hands are busy (with something other than the damn iPhone) then the mind is free to wander. And where I've been wandering around these days is space, from the macrocosm to the microcosm. For the last year I’ve been meeting regularly with a physicist and an engineer from the particle-accelerator lab at UBC and two scholars in the field of arts, for a project through Emily Carr University that explores the possibilities of 'co-thinking' or 'hybridized thinking’ between artists and scientists.  Circular patterns of the schematics of astrophysics and nuclear medicine are seen in the UBC particle-accelerator building itself. Circular patterns of the schematics of astrophysics and nuclear medicine are seen in the UBC particle-accelerator building itself. After I got over the initial shock of being invited to join the dozen research assistants on this project (having barely squeaked through Math 11 and remaining the problem child at my tax accountant's office) I realized that I would not in fact be taxed with fully grasping unfathomable ideas of space-time or the confounding mechanicals inside UBC's cavernous particle-accelerator building. Instead, my role as a facilitating artist includes producing an artwork out of this whole experiment, for a group exhibit later this winter. So why not smocking?  Material research includes reviewing the history and applications of an ages-old textile technique. Material research includes reviewing the history and applications of an ages-old textile technique. There's something zingy about using the most basic of methods — tying string knots in fabric — as I grapple with concepts like infinity, black holes, space-time, and a contracting universe. As I play with folding 540 square feet of area into volume, making a shape with no beginning nor end, I wonder about the possibility of doing the opposite of Dr. Taimina: making a model that is looking for the math. The shape that is taking shape is as convoluted as many of our group discussions, and sits in that unsettling space between pattern and chaos, structure and collapse. It's as precarious as Leaning Out of Windows, the name of this four-year co-thinking project, yet tempting enough for the possibility of catching some new views. The brilliant part about being an aging female is your growing self-acceptance. Maybe this is because you don't feel that ever-present gaze anymore so you’re not feeling as judged. Or maybe it’s because you’ve just had enough of all that and it’s tiresome and dammit you like to be cozy so screw them. Part of my self-acceptance is stepping out of the ‘should-storm’ of art-making and doing what I love to do with my hands: hunting down materials that have already had their first use and playing up their inherent qualities through knotting, weaving, tying, stitching and binding. I want to work repetitively, easily, without technological assistance and without haste or waste. And in doing so I’m carving out space and time to calm down, reflect and to think deeper — more crucial as the distractions threaten to take over.  Nate Yandle photo Nate Yandle photo In this way the work is not just in the form or connotations but the well-being and challenge that is relatable to makers who may or may not self-identify as artists. Wrapped up in there are issues of endurance, innovation, history of labour, the learning of the skill, dedication (and frustration), the specific culture and history of the method, the muscle memory that extends back to childhood, and the relationships built through the gathering of the materials. Through this making I make some hay over the established boundaries between the privileged art world and real life, between craft and sculpture, between tactile and political action. Scaffolds is composed of found spun-polyester building wrap, tarp and nylon cord over an armature of waste construction materials including caution tape, PVC piping, rebar, conduit, baling wire, and junction boxes, all attached through simple knots. Special thanks goes to the construction workers who delivered these materials from their many jobsites to my studio for my useless work with many functions. When the white RCMP SUV was spotted cruising around the Maple Street section of the community gardens early Monday morning, it was clear that the chainsaws and earth-movers were next.  Placeholders for levelled gardens: Wrap I and Wrap II, 10' diameter each, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Placeholders for levelled gardens: Wrap I and Wrap II, 10' diameter each, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) For the next three days all the gardeners of those little plots along the Arbutus rail corridor could do was ask that some of the uprooted shrubs be saved. But mostly those who had the stomach to watch the carnage were shaking their heads, hugging one another, trying not to cry. The train used to come by here when there were gardens. Now there is no need for trains yet all but a fringe of the gardens must go. It's the futility of the destruction of people's source of food, pleasure and community that hurts the most. CP has every right to their right of way, but it's a crying shame all the same.  Backhoe tracks and Wrap I, 10' diameter, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) Backhoe tracks and Wrap I, 10' diameter, crocheted Tyvek (Photo by Carlyn Yandle) When all was left was the tracks of the backhoe, I thought that laying down some giant doilies seemed appropriate. Or at least it didn't seem any more ridiculous than levelling the gardens along a useless spur where the rails have long disappeared under the tarmac of some streets it used to cross. There was no one around when I unfurled the two 10-foot-wide doilies on the bare dirt after the land-clearers left for the day - eerie for a time and place where there's usually all sorts of people tending their vegetables, walking dogs, riding bikes, pushing strollers or just surveying the spring coming on. But soon a few curious souls ventured in to ask what I was doing or snap some Instagram-destined pics. Conversations started up, mostly about Those Assholes but also about the grandmothers who loved their doilies, or the other things that these things reminded them of. A bit of absurdity in the face of absurdity, but it kick-started something. When one's world seems unbearable "it is the sublime madness that makes one sing," Pulitzer-prize-winning war correspondent/author/minister Chris Hedges told the crowd at a packed downtown church two weeks ago. Acts of creative expression in the face of devastation are signs of a belief in a "divine justice." They are small acts of hope that say, 'We exist.' Hedges rocks your world view here (talk begins at 16-minute mark):  After a long and often painful labour, I’m happy to introduce…the twins! I’m not sure why I plumped up the two eight-foot-wide doilies, freshly completed today, for their first picture. It might have something to do with this morning’s mammogram. ‘Why’ is always a scary question wherever conception is concerned. ‘What’ and ‘how’ are a little more manageable. What they are are two crocheted doilies on a scale of 1 inch = 1 foot, using a material that mimics the relative volume, appearance and weight of the cotton floss called for in the original patterns for the two table-top doilies I found in my stack of 1950s homemaker magazines.  What material was a tough enough question without the Why lurking behind. I’d been searching for the right stuff for ages until I realized it was all around me. In fact, I’d been hammering cedar shingles into it for weeks at a time last summer: Tyvek exterior building wrap. I pushed the Why away as I special-ordered a 100-yard bolt of the wrap. The size of the doilies was determined by the biggest crochet hook I could get my hands on (and could handle). After making several swatches I finally decided two-inch strips were sufficiently doilyish. Scraping up any residual knowledge of basic math that has clung to my grey matter, I have conjured up this probably-incorrect calculation of length of materials used, in answer to the What:  36 inches (1 yard width) ÷ 2-inch strips = 18 strips x 60 inches (length) = 1080 linear inches per yard x 95 yards (100-yard bolt minus remaining five yards) = 102,600 linear inches ÷ 12 inches = 8,550 feet ÷ 2 doilies = 4,275 linear feet per doily. (I love how stats can be simultaneously unfathomable and banal.) How did I know how to make doilies? Let me count the ways in all those crappy/crafty afghans, potholders, slippers, placemats, doll clothes, stuffed animals, toques, nerdy vests and that abortion of a bikini. Why the giant doily, you/I insist? Because it was there, in my head. I conceived two to enjoy their similarities and their differences. Go forth, twins! Find your purpose! Write if you get a show! And don’t let the why-ers get you down! |

Sharing on the creative process in long-form writing feels like dog-paddling against the tsunami of disinformation, bots, scams, pernicious sell sites and other random crap that is the internet of today. But I miss that jolt of inspiration from artists sharing their work, ideas and related experiences in personal, non-marketing blogs, so I'm doing my part.

browse by topic:

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed