Click HERE for a 10-minute journey through the methods and motivations behind this MFA thesis. (Film made by Ana Valine, Rodeo Queen Pictures, August 2020)

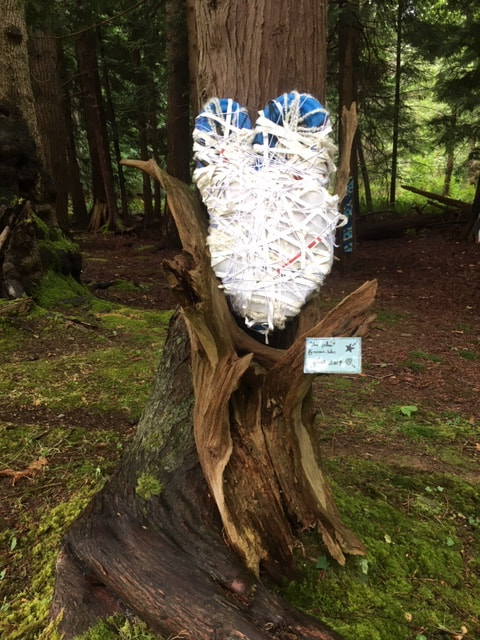

Everyone is feeling that relentless creep of plastic that is threatening to consume us, the consumers. I felt myself drowning in the tsunami of stuff over this past year of grad studies at Emily Carr University. Art, as one instructor stated, is a wasteful business. Even as I retreated back to my green, pristine Gulf Island I was hit with it at the end of the long drive through forest to the local dump: a mountain of garbage. This, from a small off-grid community known for its environmental consciousness. My art practice is driven by a need to physically grapple with the unfathomable when words are not enough. In the strange way that an idea for an artwork takes hold, that sight of that mountain of petroleum-derived recycling-rejects led to my latest project: Foundlings. For a while I’d been trying to land on a low-barrier, low-skill technique that could involve kids in the making of objects from found, non-recyclable and non-biodegradable materials. Then I landed on the work of late American sculptor Judith Scott, whose many exhibitions of her curious bound and woven fiber/found objects have led to discourse on “outsider” art, disability (she was profoundly deaf, non-verbal, and had severe Down’s Syndrome), intention, new sculpture forms and the privileged art world. Within a month of escaping the art institution I was driving a pickup-truckload of colourful non-recyclable, non-biodegradable bits from the home-grown garbage mountain to the island’s only elementary school. Before we got to the making part I sat down with the students and shared some images of Scott’s work for inspiration. We talked about how this artist’s method of wrapping, binding and weaving fibre around objects adds curiosity to what is on the inside. We talked about how working with familiar objects and materials in unusual ways can lead to new ideas. And we talked about how an object can be terrible and beautiful at the same time, does not have to be a recognizable thing nor have utility. We worked over time on the pieces, some kids on their own and some in groups of two or three, adding even more fibre and found plastic detritus from their year-end trip to the local provincial marine park. On the final day of school I arrived to pick up the final pieces and was astounded at the creations. They were richly textured, humorous and foreboding, and proof of why I collaborate with children: they consistently demonstrate the importance of letting hands and imaginations fly.

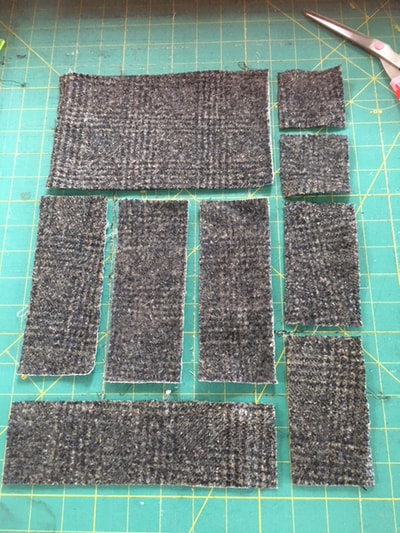

They each titled their pieces in their own hand and I installed them for exhibit on forest plinths (moss-covered stumps from the last big clearcut) in time for the annual Arts Fest. With no chance they’ll degrade in the weather they remain there, pretty and pretty disturbing: our inescapable stuff. At first I thought all this must still be debris from the Japan tsunami. But that was eight years ago and the surf in my remote neck of the woods keeps throwing up snarls of monofilament netting, plastic shards, nylon rope, bits of fibreglass hulls, and styrofoam. So much styrofoam. I’ve been collecting up the stuff, inspired by this Gulf island’s own Styrophobe who’s taken on what some would say is a Sisyphean task of removing even the tiny beads of polystyrene from the clefts of rock along the shoreline. My gathering is a tiny, maybe even futile, gesture but I’m giving form to the invisible: the bits and pieces we overlook on the foreshore or in the forest that, when lashed, bound, and woven together demand attention. These small but critical masses of debris are inspired by the found-material sculptures of Judith Scott. As I lash, bind, and weave I think of how the kids in my life would like to be in on this: hunting for material, making form from their hands and imaginations. My gathering requires connecting with others to access materials. The Styrophobe, who’s also the guy in charge of the local dump, stands on the top of the garbage mountain, holding up uncertain objects for my consideration: How’s this? This stuff looks pretty good. Could you use this? In 15 minutes I fill the back of the pickup truck with a curated collection of colourful plastic throwaways: pool noodles, watering cans, yards of orange fencing, jerrycans, twine, tape, cleaning-pad refill boxes, five-gallon buckets and lids. I fill up with purple things, red things, plastics in acid green, electric blue, hazard yellow, and caution orange — all the colours of the petrochemical rainbow. After a lot of material prep (cutting off snags and sharp bits, wiping and washing off surface debris), I haul it to the local school where the kids, teacher and I dive in and play with the unwanted stuff. We have plans and we don’t have a plan, which is the right place to be with material exploration. This is where we learn to work with each material and not against its inherent nature, a great reminder of the futility of forcing solutions. This is where we learn to follow our hands, to work on our own or collectively over days and not minutes, to consider colour, form, and techniques for putting it all together, to create something that resonates with this time and place out of nothing anybody wanted. It’s an important start for the generation that will be forced to deal with this legacy of stuff long after the plastic-agers die off.  There ought to be an international law against the dirty business of jeans manufacturing. It poisons waterways, mainly in China, prompting environmental groups to raise the alarm against the devastation to communities and local ecosystems, yet consumers around the world continue to cycle through jeans, for work and in slavish loyalty to fashion trends. Even on the small off-the-grid Gulf island of Lasqueti where I do much of my work, there is a constant oversupply of denim at the local Free Store. Too ugly or thrashed to be snapped up for the price of zero, they are destined for the landfill where the toxic dyes are left to leach into the ground.  Jeans reflect the West Coast palette. Carlyn Yandle photo Jeans reflect the West Coast palette. Carlyn Yandle photo But, honestly, if they weren't so pretty, I wouldn't be saving them from the dump. It's that very West Coast denim palette that compels me to rescue these ripped, stained or just outdated jeans, skirts, jackets and dresses and mess with them. For the past few years I've been cutting them into usable pieces and sewing up utility items — bags, oven mitts, hot-pot mats, lumbar cushions — and before long I fell into my own tiny cottage industry stitching up utility aprons. Lately I've been working them up in quilts of high-contrast hues with frayed exposed seams or muted reverse greys, all in conversation with the coastal views just beyond my sewing table. So for environmental reasons and the pretty, durable nature of old denim, I keep innovating new uses, but my explorations into non-utility pieces (the stuff we call Art) is more about the culture embedded in all those jeans: the worn knees, the rips, the stains that all speak to the physical work people do on this off-the-grid island community to sustain them. I dabbled with undulating appliquéd fields inspired by the coastal climate and vistas but lately I've been more interested in exploiting the sculptural possibilities of this weighty, stiff fabric. Enter my latest exploration: large-scale macrame.  Knotting seemed like a natural way to enhance dimension, and it's relevant to this island community where knowing a few useful knots is an essential skill and in wide evidence. It also speaks to the late-'60s/early '70s back-to-the-land counterculture that defines Lasqueti. I liked the idea of creating a large-scale fringe for this place on the fringes of urban life. (Fun fact: The 13th-century Arabic weavers' word for "fringe" is "migramah", which eventually became known as "macrame".) I gave myself some rules of engagement (like I do) to create a pattern. 1) The strands would be all three-inch strips. 2) The overall length would be largely determined by the number of strips I could squeeze out of an average size of jeans. 3) I would work from dark jeans to light to dark fabrics, to create a highlight in the centre of the piece. 4) The overall width of this super-fringe would be determined by the piece of driftwood I selected. Fifty-five hours of knotty work later I completed 28 Jeans: Denim Ombré, a wall-mounted macrame work that continues to inspire more ideas and more questions: How can I achieve a more sculptural effect? How can I find that beautiful place between pattern and collapse? And most importantly: Why did I throw away my old macrame magazines?? Materialistic. People say it like it's a bad thing. But there's not necessarily anything selfish or hoardy or wasteful about feeling deeply connected to materials. If we all started being a little more materialistic we might not be now contending with the Great Pacific Garbage Patch or space junk. I want no part with parting so quickly from one-use-life materials when a meaningful second life is possible. So when a couple of people dear to my heart were clearly torn about parting with some favourite clothes of their loved ones who recently passed away — one within this year, the other within 18 months — I felt it too. These bits of cloth are interwoven with the memory of the wearer, his style, the special occasions and the everyday. Just looking at them hanging in the back closet brought the son, the wife, to tears. Some of that emotion is also about feeling at odds with what to do with it all. Yet holding onto useless things, especially in this town where we're so squeezed for space we have to go outside our living spaces just to change our mind, can even bring on some shame or panic that we can't let go, move on. I felt the potency of the pieces too, and suggested selecting a few items to be repurposed into something that would bring comfort, and in remembrance. The first project this spring was the Great-Grandfather Quilt, for the first of the next generation who missed meeting his great-grandfather by 9 months. The second was Dad's Blanket, which lives on one of the two matching sofas where father and son watched the baseball in his last three years. The third is a lumbar-support cushion made from silk ties that's parked on his wife's favourite reading chair. It takes a bit of faith to allow those blazers and sweaters, ties and dress shirts to leave their dark cupboards and be subjected to my fibre-art experiments but I'm grateful they did. It was a little unnerving, plunging wool blazers into a hot-water-wash and tumble-dry, or severing several silk neckties in one swipe of the rotary cutter, but that's the deal with making and innovating: sometimes you have to take a deep breath and boldly go, risking failure. And there is definitely failure in all of this making. Design changes happen on the fly, dictated by odd dimensions of the pieces and unpredictable fabric behaviour. (It's a thing.) Trying to wrestle slippery bias-cut silk, unstable cashmere knit and coat-heavy woven wool into submission enough to lie flat together is a test of one's patience. The trick is to embrace imperfection and keep the big picture in mind. I think about the Gees Bend quilters I saw a few years ago at Granville Island and the gospel spiritual song two of them sang at the start of their talk, and I say a little prayer myself: God I hope this works.

The other challenge is creating works that resonate with the spirit of the original wearer, so it's not just a matter of chopping up the clothing into tiny unidentifiable pieces to be re-fabricated in a generic quilt. You don't want to be too literal either, appliquéing ties into a Ties Quilt or (creepier) using every last button and pocket or (horrors) just sewing all the clothes together into a blanket or something. Binding the one blanket with necktie fabric and appliquéing the suit labels in one corner of an army blanket backing (for the man who served in the US Army) felt like the right balance. I post each Remembrance Pieces project on Facebook to inspire other material girls and guys, and to pay my respects to the stuff of life and to those of this life no longer. “Your hair seems blue,” a friend noted over dinner. It really is. I’ve joined the blue-rinse gang — emphasis on the blue. Denim blue is an unnatural hair hue that seems only natural now that I'm surrounded by heaps of old jeans and altering all those tones of denim. As usual, I’m not questioning why, but how: how to add some pleasing form to a traditional working fabric; how to infuse some lacy aspect into that utilitarian cloth.  What I do see is that after four months exposed to the bright colours of urban Mexico and the glare of the garish new Trump era, I am thirsty for cool, serene tones and patterns of rain-soaked skies and coastal stones rolled smooth by the sea. I returned to discover that I am, in fact, attached to the world of hot-water bottles, mugs of tea and toasty quilts, the coziness against the cold. Blue is my touchstone: something real and eternal to cling to in these uncertain, unfathomable times. I may be seduced by sun-baked yellow, spicy red, lethal lime green and sunset pink but my deep, serene dreams are all denim blue. (For a sample of my blue-jean fabrications, check out my other site, Workwraps.weebly.com) Below: Recent experiments with denim include dousing doilies in bleach and imprinting them on on jeans before cutting for quilts.

It feels like the Internet has killed the fun of taking snapshots of beautiful cities and people. So many times over the last four months in Mexico I've raised my camera (phone) to capture an impressive bronze sculpture or some baroque church facade then thought: This is pointless. A Google-image search with a few key words (Guanajuato, musicians, Don Quixote, Pipila) would produce hundreds of better-quality stock photos. We're saturated in instagrammable images. I miss those old pocket travel photo albums.

This might explain all the selfie sticks threatening to take your eye out in the crowded plazas on any given night here; putting yourself in the picture with all the famous stuff behind will guarantee a unique photo. So I have very little in terms of a photographic record for my time here. Every view of the strolling musicians in the plazas, or the teenage girls decked in ballgowns for their quinceanera (debut) parties, the food vendors, the street singers dressed in Renaissance-style hose and puffed velvet jackets are already done. So done. Then last week I finally started to see that the one signature-Guanajuato element that I've been captivated by is actually a worthy photo subject: the retaining walls that barely seem to be holding back the jumble of colourful, cubic houses clinging to the surrounding hills. There's a compelling visual story in those layers of peeling paint on crumbling plaster on adobe bricks stacked on crudely cut limestone foundations. The traces of human activity in one section of wall speaks to the human habitation in this city that has its roots in the 1500s. It's quite a study in social history and handwork, an unplanned, almost invisible beauty, especially to a tourist whose port town of Vancouver has been replaced by a gleaming, pristine city of glass. I'm seeing them as found abstracts, images of unintentional collages and mixed-media works by generations of people who work with their hands. It is excruciating to junk a piece of, well, in this case, junk. But it has to be done. Such is the reality of the Vancouver maker who likes to work large but lives in a small space. So I sacrifice Charm Bracelet, following the end of its one and only showing at the premiere exhibit of the AgentC Gallery in Surrey this week.  I'm actually hoping that some other people will junk this on my behalf because I don't trust myself. I may, at the last minute, decide to keep it for future shows. Even as a tinny little voice in my head pleads, Don't toss me out; I'm part of you. Don't abandon part of you! the more practical adult is adamant: Do not burden your future with this heavy, rusty chain of old bed springs and rusty tools. The whole dilemma is fitting for this piece designed to evoke ideas of memory and weight, of hoarding and stashing (the materials were found in a Surrey residential lot, just a small fraction of household junk dumped by the former owner). It speaks to our attachment to useless things that are dragging us down. Got it: lose the stuff, embrace the space. I will not sabotage the plan. Not this time. Really. Just for the record, my Toybits were created far, far before Mad Max: Fury Road hit the theatres — although the resemblance of those Metallica-esque assault vehicles to my small sculptures is uncanny.

For some inexplicable reason (even to myself) I have been collecting the toy fragments that appear to follow in the wake of my Lego-loving nephews (and one pint-sized niece) for some years now. I sorted them by colour and last year started binding them together with found fiber-optic wiring of the same colour. The right size seems to be about 14 inches wide or high. Any more and the inner bits become obscured; any less and they seem unfinished. I imagined these colour assemblages as live models for abstract painting — which would make those paintings not abstracts at all, but figurative works. That inherent contradiction adds to the confoundedness of these pieces that are actually put together like puzzles, with each piece added as they 'fit' onto the plastic mass. After I inhaled the visually delicious Mad Max movie, I wondered how the Toybits series, six of which are now on display at Port Moody Arts Centre gallery until Sept. 28, would look at a fearsome scale. I made a playdate with Mr. Photoshop in some new virtual landscapes. Voila....  "Unfixtures": Found lamp bases, utensils, gesso. "Unfixtures": Found lamp bases, utensils, gesso. I liked the idea of messing with the overlooked and the banal to open up possible new understandings about preconceived notions. There was something delicious about a collection of attractive objects -- flat white familiar forms at a personal/counter-top scale -- that is also just a little disturbing for its wrongness. Those little electrical cords suggest hazard. They seem to say, Whatever you do, don't plug us in, so in a sense they have some visual power. I was thinking about Martha Rosler's groundbreaking feminist video, "Semiotics of the Kitchen" (1975 - edited version below) when I came up with my "Unfixtures" sculpture series. Ah, the power of uncertain objects. What was an experiment in found-object sculpture is an eye-catching visual for a company in the business of creative work.  Eggbeater Creative's new brochure (Clay Yandle photo) Eggbeater Creative's new brochure (Clay Yandle photo) "I love the plug part," my brother Clay said in a text the other day, after sending me pics of his company's latest brochures and business cards. "It makes it real... like you could fire it up and it would start doing whatever the hell it would do." Unfixtures are a permanent fixture (when they're not showing in a gallery) at my brother's office. One of the pieces in particular seemed to be speaking to him as he was trying to come up with a name for a new web-design/branding partnership a while back. "It was the perfect storm of me trying so hard to come up with a name and just staring at the sculpture led me to understand how this business was the mix of two companies," he wrote. eggbeater creative was born. "It was whimsical and interesting, and then there was the obvious part of the eggbeaters working as light bulb (idea) metaphors. The sculpture had traditionally conflicted parts, but they were together in a way that worked." The company logo (seen at the bottom left of the brochure in this image) riffs on the sculpture and the lower-case 'e'. Below: A time-lapsed view of a painting commissioned for Eggbeater Creative: |

Sharing on the creative process in long-form writing feels like dog-paddling against the tsunami of disinformation, bots, scams, pernicious sell sites and other random crap that is the internet of today. But I miss that jolt of inspiration from artists sharing their work, ideas and related experiences in personal, non-marketing blogs, so I'm doing my part.

browse by topic:

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed