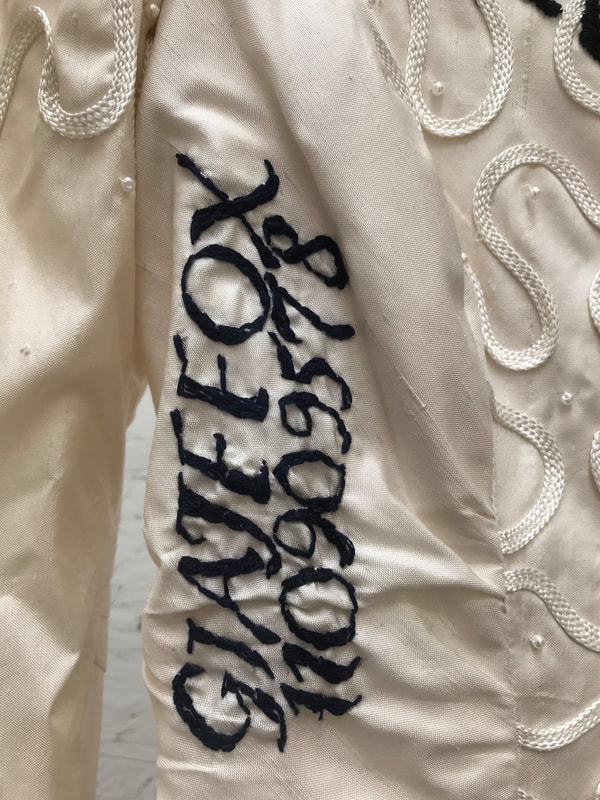

It is a ballerina-length A-line number, a fitted silhouette of crisp, Japanese Dupioni silk festooned with faux pearls, featuring a winding pattern of woven ivory ribbon stitched around the shoulder and ruche bodice, and bateau neckline edged with mini pearls. A strand of 14 pearl shank buttons nestles into handmade button loops running down the back, disappearing into a bustle of box pleats. A puff of shoulder sleeve slims to a fitted forearm, leading down to three more pearl buttons and ending in a pointed edge at the wrist edged in more pearl trim. The pattern was painstakingly customized by the maid of honour, possibly still this city’s most skilled professional in design development. The sleeve itself is an architectural feat, with three delicate darts at the elbow and invisible underarm gusset for ease of movement when slow-dancing.

The dress was a big effin' deal, is what I'm saying.

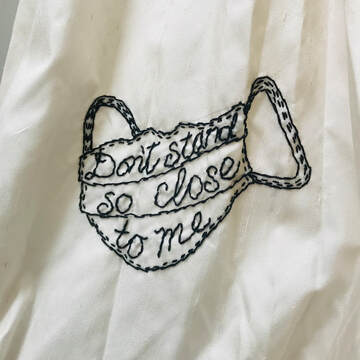

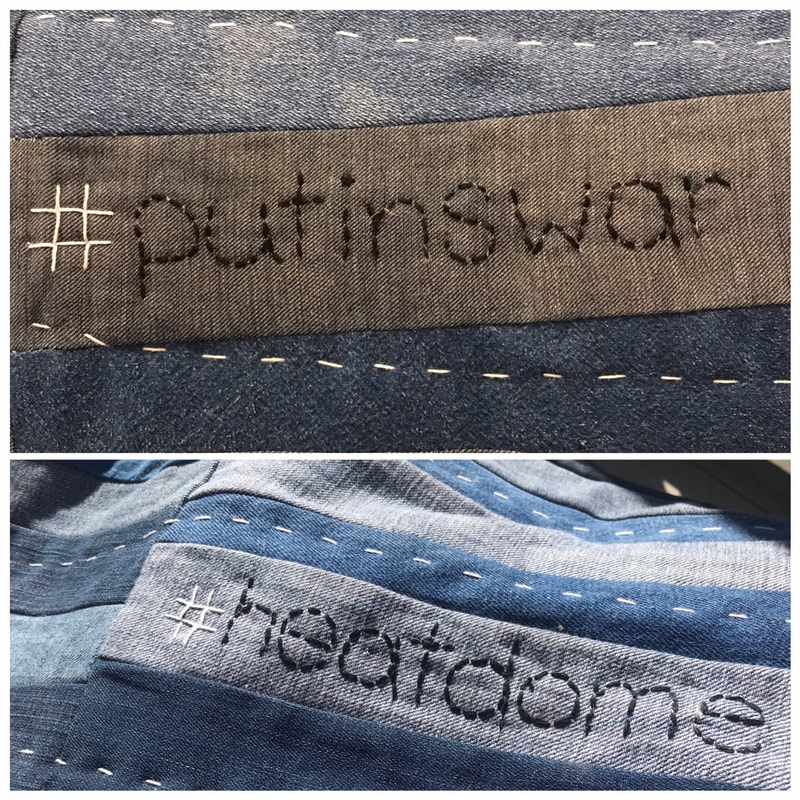

Covid-era expression

Covid-era expression

My first job as a full-time newspaper reporter included re-writing submitted wedding announcements — a bit of a comedown after an intensive year of journalism school wrestling with ethical issues and the craft of long-form investigative reporting. Banging out descriptions of sweetheart necklines and fingertip veils was tedious work that made me crabby.

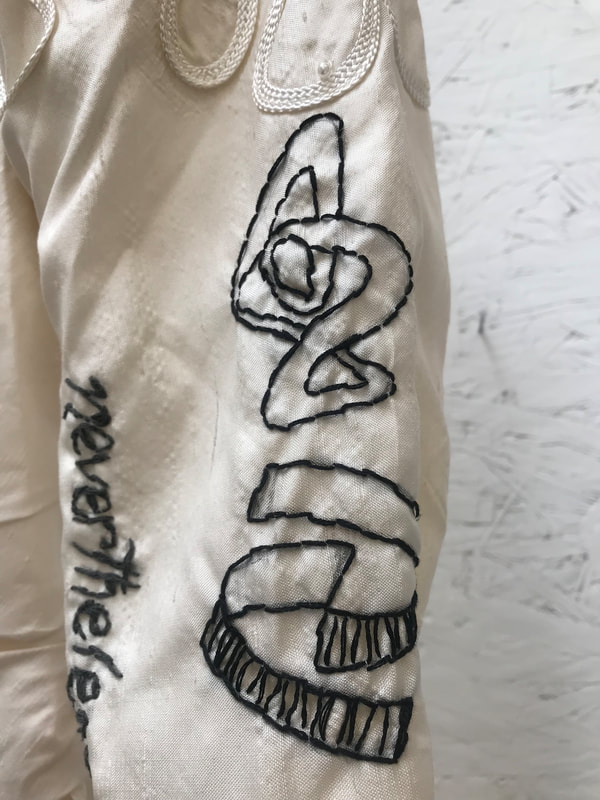

"Nevertheless, she persisted", a Trump-era memento

"Nevertheless, she persisted", a Trump-era memento I’m not nostalgic about the whole patriarchal wedding ritual and its objectifying notions of purity but I did love that dress. Whenever I re-organized my deep storage I would unfurl it from its wrappings, a little ashamed at my attachment to the thing. I needed to poke holes into the whole notion; I needed to break through this pure silk skin.

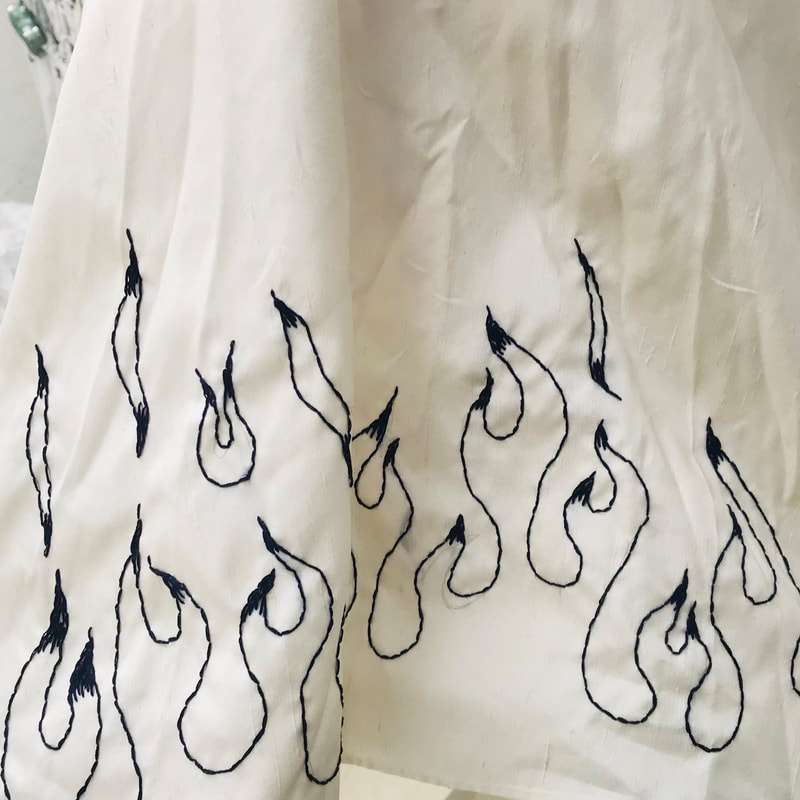

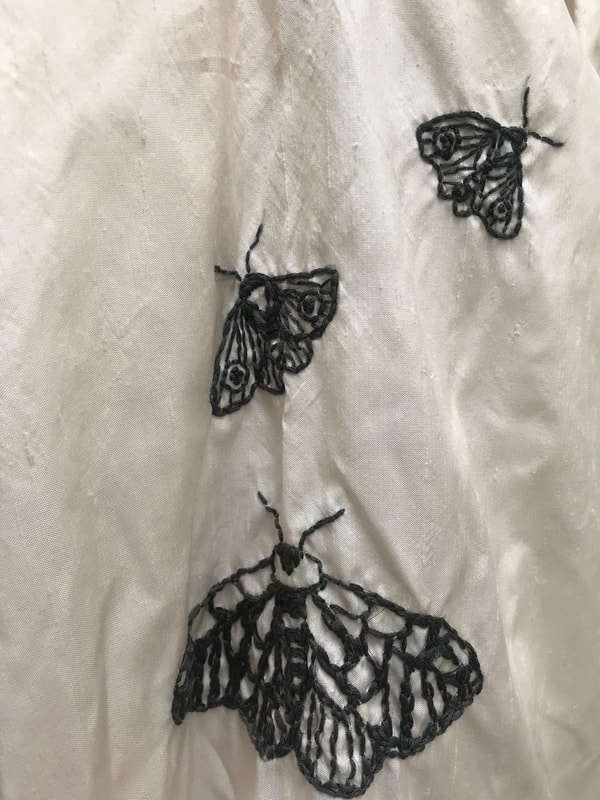

I texted a friend for support, someone whose own actual skin is needled with ink here and there like it’s no big deal. Do it. Why not just do it?, she texted back. I took a deep breath and plunged the needle into the silk, embedding stitches of ink-black embroidery floss into the ivory cloth. I winced at the first piercing but like tattoos, there was also a flood of pleasure. I began embroidering significant moments of this significant era then hung it on a hanger in my studio until another compulsion came on. This is how this dress and I work together now: it is a work in progress, like that bride who is always still becoming.

I feel zingy about this mark-making with no overall plan that will not be erased, this disruption of expectations for young women — of my time and place, at least. Unbridled is a work in progress, an unkempt keeper, that weaves the pain in with the pleasure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed